"Susan B. Anthony is not on trial; the United States is on trial."--Matilda Joslyn Gage

More than any other woman of her generation, Susan B. Anthony saw that all of the legal disabilities faced by American women owed their existence to the simple fact that women lacked the vote. When Anthony, at age 32, attended her first woman's rights convention in Syracuse in 1852, she declared "that the right which woman needed above every other, the one indeed which would secure to her all the others, was the right of suffrage." Anthony spent the next fifty-plus years of her life fighting for the right to vote. She would work tirelessly: giving speeches, petitioning Congress and state legislatures, publishing a feminist newspaper--all for a cause that would not succeed until the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment fourteen years after her death in 1906.

She would, however, once have the satisfaction of seeing her completed ballot drop through the opening of a ballot box. It happened in Rochester, New York on November 5, 1872, and the event--and the trial for illegal voting that followed--would create a opportunity for Anthony to spread her arguments for women suffrage to a wider audience than ever before.

The Vote

Anthony had been planning to vote long before 1872. She would later state that "I have been resolved for three years to vote at the first election when I had been home for thirty days before." (New York law required legal voters to reside for the thirty days prior to the election in the district where they offered their vote.) Anthony had taken the position--and argued it wherever she could--that the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment gave women the constitutional right to vote in federal elections. The Amendment said that "all persons born and naturalized in the United States...are citizens of the United States," and as citizens were entitled to the "privileges" of citizens of the United States. To Anthony's way of thinking, those privileges certainly included the right to vote.

On November 1, 1872, Anthony and her three sisters entered a voter registration office set up in a barbershop. The four Anthony women were part of a group of fifty women Anthony had organized to register in her home town of Rochester. As they entered the barbershop, the women saw stationed in the office three young men serving as registrars. Anthony walked directly to the election inspectors and, as one of the inspectors would later testify, "demanded that we register them as voters."

The election inspectors refused Anthony's request, but she persisted, quoting the Fourteenth Amendment's citizenship provision and the article from the New York Constitution pertaining to voting, which contained no sex qualification. The registers remained unmoved. Finally, according to one published account, Anthony gave the men an argument that she thought might catch their attention: "If you refuse us our rights as citizens, I will bring charges against you in Criminal Court and I will sue each of you personally for large, exemplary damages!" She added, "I know I can win. I have Judge Selden as a lawyer. There is any amount of money to back me, and if I have to, I will push to the 'last ditch' in both courts."

The stunned inspectors discussed the situation. They sought the advice of the Supervisor of elections, Daniel Warner, who, according to thirty-three-year-old election inspector E. T. Marsh, suggested that they allow the women to take the oath of registry. "Young men," Marsh quoted Warner as saying, "do you know the penalty of law if you refuse to register these names?" Registering the women, the registrars were advised, "would put the entire onus of the affair on them." Following Warner's advice, the three inspectors voted to allow Anthony and her three sisters to register to vote in Rochester's eighth ward.

Testifying later about the registration process, Anthony remembered "it was a full hour" of debate "between the supervisors, the inspectors, and myself." In all, fourteen Rochester women successfully registered that day, leading to calls in one city paper for the arrest of the voting inspectors who complied with the women's demand. The Rochester Union and Advertiser editorialized in its November 4 edition: "Citizenship no more carries the right to vote that it carries the power to fly to the moon...If these women in the Eighth Ward offer to vote, they should be challenged, and if they take the oaths and the Inspectors receive and deposit their ballots, they should all be prosecuted to the full extent of the law."

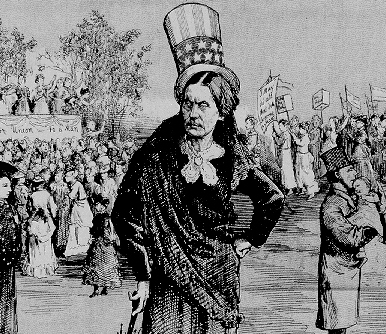

Sketch of women voting

Soon after the polls opened at the West End News Depot on Election Day, November 5, Anthony and seven or eight other women cast their ballots. Inspectors voted two to one to accept Anthony's vote, and her folded ballot was deposited in a ballot box by one of the inspectors. Inspector E. T. Marsh testified later as to feeling caught between a rock and a hard place: "Decide which way we might, we were liable to prosecution. We were expected...to make an infallible decision, inside of two days, of a question in which some of the best minds of the country are divided." Seven or eight more women of Rochester successfully voted in the afternoon. Anthony's vote went to U. S. Grant and other Republicans, based on that party's promise to give the demands of women a respectful hearing. Later that day, Anthony would write of her accomplishment to her close friend and fellow suffragist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton:

Dear Mrs Stanton

Well I have been & gone & done it!!--positively voted the Republican ticket--strait this a.m. at 7 Oclock--& swore my vote in at that--was registered on Friday....then on Sunday others some 20 or thirty other women tried to register, but all save two were refused....Amy Post was rejected & she will immediately bring action for that....& Hon Henry R. Selden will be our Counsel--he has read up the law & all of our arguments & is satisfied that we our right & ditto the Old Judge Selden--his elder brother. So we are in for a fine agitation in Rochester on the question--I hope the morning's telegrams will tell of many women all over the country trying to vote--It is splendid that without any concert of action so many should have moved here so impromptu--

The Democratic paper is out against us strong & that scared the Dem's on the registry board--How I wish you were here to write up the funny things said & done....When the Democrat said my vote should not go in the box--one Republican said to the other--What do you say Marsh?--I say put it in!--So do I said Jones--and "we'll fight it out on this line if it takes all winter"....If only now--all the women suffrage women would work to this end of enforcing the existing constitution--supremacy of national law over state law--what strides we might make this winter--But I'm awful tired--for five days I have been on the constant run--but to splendid purpose--So all right--I hope you voted too.

Affectionately,

Susan B. Anthony

Arrest and Indictment

The votes of Susan Anthony and other Rochester women was a major topic of conversation in the days that followed. In a November 11 letter to Sarah Huntington, Anthony wrote: "Our papers are discussing pro & con everyday." Anthony occupied much of her time meeting with lawyers to discuss a planned lawsuit by some of the women whose efforts to register or vote were rejected.

Meanwhile, a Rochester salt manufacturer and Democratic poll watcher named Sylvester Lewis filed a complaint charging Anthony with casting an illegal vote. Lewis had challenged both Anthony's registration and her subsequent vote. United States Commissioner William C. Storrs acted upon Lewis's complaint by issuing a warrant for Anthony's arrest on November 14. The warrant charged Anthony with voting in a federal election "without having a lawful right to vote and in violation of section 19 of an act of Congress" enacted in 1870, commonly called The Enforcement Act. The Enforcement Act carried a maximum penalty of $500 or three years imprisonment.

The actual arrest of Anthony was delayed for four days to allow time for Storrs to discuss the possible prosecution with the U. S. Attorney for the Northern District of New York. On November 18, a United States deputy marshal showed up at the Anthony home on Madison Street in Rochester, where he was greeted by one of Susan's sisters. At the request of the deputy, Anthony's sister summoned Susan to the parlor. Susan Anthony had been expecting her visitor. As Anthony would later tell audiences, she had previously received word from Commissioner Storrs "to call at his office." Anthony's response was characteristically plainspoken: "I sent word to him that I had no social acquaintance with him and didn't wish to call on him."

At the May meeting of the National Women's Suffrage Association, Anthony described what happened when the deputy marshal, "a young man in beaver hat and kid gloves (paid for by taxes gathered from women)," came to see her:

He sat down. He said it was pleasant weather. He hemmed and hawed and finally said Mr. Storrs wanted to see me...."what for?" I asked. "To arrest you." said he. "Is that the way you arrest men?" "No." Then I demanded that I should be arrested properly. [According to another account, Anthony at this point held out her wrists and demanded to be handcuffed.] My sister desiring to go with me he proposed that he should go ahead and I follow with her. This I refused, and he had to go with me. In the [horse-drawn] car he took out his pocketbook to pay fare. I asked if he did that in his official capacity. He said yes; he was obliged to pay the fare of any criminal he arrested. Well, that was the first cents worth I ever had from Uncle Sam.

Anthony was escorted to the office of Commissioner Storrs, described by Anthony as "the same dingy little room where, in the olden days, fugitive slaves were examined and returned to their masters." Upon arriving, Anthony was surprised to learn that among those arrested for their activities on November 5 were not only the fourteen other women voters, but also the ballot inspectors who had authorized their votes.

Anthony's lawyers refused to enter a plea at the time of her arrest, and Storrs scheduled a preliminary examination for November 29. At the hearing on the 29th, complainant Sylvestor Lewis and Eighth Ward Inspectors appeared as the chief witnesses against Anthony. Anthony was questioned at the hearing by one of her lawyers, John Van Voorhis. Van Voorhis tried to establish through his questions that Anthony believed that she had a legal right to vote and therefore had not violated the 1870 Enforcement Act, which prohibited only willful and knowing illegal votes. Anthony testified that she had sought legal advice from Judge Henry R. Selden prior to casting her vote, but that Selden said "he had not studied the question." Van Voorhis asked: "Did you have any doubt yourself of your right to vote?" Anthony replied, "Not a particle." Storrs adjourned the case to December 23.

After listening to legal arguments in December, Commissioner Storrs concluded that Anthony probably violated the law. When Anthony--alone among those charged with Election Day offenses--refused bail, Storrs ordered her held in the custody of a deputy marshal until the grand jury had a chance to meet in January and consider issuing an indictment. Anthony saw the commissioner's decision as a ticket to Supreme Court review, and began making plans with her lawyers to file a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. In a December 26 letter, Anthony wrote confidently, "We shall be rescued from the Marshall hands on a Writ of Habeas Corpus--& case carried to the Supreme Court of the U. S.--the speediest process of getting there." Already letters were coming in with contributions to her "Defense Fund." She was anxious to put the money to use.

By early January, Anthony was already trying to make political hay out of her arrest. She sent off "hundreds of papers" concerning her arrest to suffragist friends and politicians. She still, however, found her situation difficult to comprehend: "I never dreamed of the U. S. officers prosecuting me for voting--thought only that if I was refused I should bring action against the inspectors-- But "Uncle Sam" waxes wroth with holy indignation at such violation of his laws!!"

Anthony's attorney, Henry Selden asked a U. S. District Judge in Albany, Nathan Hall, to issue a writ of habeas corpus ordering the release of Anthony from the marshal's custody. Hall denied Selden's request and said he would "allow defendant to go to the Supreme Court of the United States." The judge then raised Anthony's bail from $500 to $1000. Anthony again refused to pay. Selden, however, decided to pay Anthony's bail with money from his own bank account. In the courtroom hallway following the hearing Anthony's other lawyer, John Van Voorhis, told Anthony that Selden's decision to pay her bail meant "you've lost your chance to get your case before the Supreme Court." Shaken by the news, Anthony confronted her lawyer, demanding that he explain why he paid her bail. "I could not see a lady I respected put in jail," Selden answered.

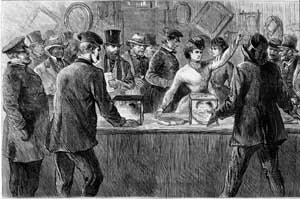

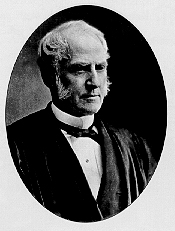

Henry Selden, Anthony's attorney

A disappointed Anthony still had a trial to face. On January 24, 1873, a grand jury of twenty men returned an indictment against Anthony charging her with "knowingly, wrongfully, and unlawfully" voting for a member of Congress "without having a lawful right to vote,....the said Susan B. Anthony being then and there a person of the female sex." The trial was set for May.

On the Stump

Anthony saw the four months until her trial as an opportunity to educate the citizens of Rochester and surrounding counties on the issue of women suffrage. She took to the stump, speaking in town after town on the topic, "Is it a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?"

By mid-May, Anthony's exhausting lecture tour had taken her to every one of the twenty-nine post office districts in Monroe County. To many in her audience, Anthony was the picture of "sophisticated refinement and sincerity." The fifty-two-year-old suffragist delivered her earnest speeches dressed in a gray silk dress a white lace collar. Her smoothed hair was twisted neatly into a tight knot. She would look at her audience, ranging from a few dozen to over a hundred persons, and begin:

Friends and Fellow-citizens: I stand before you to-night, under indictment for the alleged crime of having voted at the last Presidential election, without having a lawful right to vote. It shall be my work this evening to prove to you that in thus voting, I not only committed no crime, but, instead, simply exercised my citizen's right, guaranteed to me and all United States citizens by the National Constitution, beyond the power of any State to deny.

In her address, Anthony quoted the Declaration of Independence, the U. S. Constitution, the New York Constitution, James Madison, Thomas Paine, the Supreme Court, and several of the leading Radical Republican senators of the day to support her contention that women had a legal right as citizens to vote. She argued that natural law, as well as a proper interpretation of the Civil War Amendments, gave women the power to vote, as in this passage suggesting that women, having been in a state of servitude, were enfranchised by the recently enacted Fifteenth Amendment extending the vote to ex-slaves:

And yet one more authority; that of Thomas Paine, than whom not one of the Revolutionary patriots more ably vindicated the principles upon which our government is founded:

"The right of voting for representatives is the primary right by which other rights are protected. To take away this right is to reduce man to a state of slavery; for slavery consists in being subject to the will of another; and he that has not a vote in the election of representatives is in this case...."

Is anything further needed to prove woman's condition of servitude sufficiently orthodox to entitle her to the guaranties of the fifteenth amendment? Is there a man who will not agree with me, that to talk of freedom without the ballot, is mockery--is slavery--to the women of this Republic, precisely as New England's orator Wendell Phillips, at the close of the late war, declared it to be to the newly emancipated black men?

Anthony ended her hour-long lectures by frankly attempting to influence potential jurors to vindicate her in her upcoming trial:

We appeal to the women everywhere to exercise their too long neglected "citizen's right to vote." We appeal to the inspectors of elections everywhere to receive the votes of all United States citizens as it is their duty to do. We appeal to United States commissioners and marshals to arrest the inspectors who reject the names and votes of United States citizens, as it is their duty to do, and leave those alone who, like our eighth ward inspectors, perform their duties faithfully and well.

We ask the juries to fail to return verdicts of "guilty" against honest, law-abiding, tax-paying United States citizens for offering their votes at our elections. Or against intelligent, worthy young men, inspectors of elections, for receiving and counting such citizens votes.

We ask the judges to render true and unprejudiced opinions of the law, and wherever there is room for a doubt to give its benefit on the side of liberty and equal rights to women, remembering that "the true rule of interpretation under our national constitution, especially since its amendments, is that anything for human rights is constitutional, everything against human right unconstitutional."

And it is on this line that we propose to fight our battle for the ballot-all peaceably, but nevertheless persistently through to complete triumph, when all United States citizens shall be recognized as equals before the law.

Anthony's lecture tour plainly worried her prosecutor, U. S. Attorney Richard Crowley. In a letter to Senator Benjamin F. Butler, Anthony wrote, "I have just closed a canvass of this county--from which my jurors are to be drawn--and I rather guess the U. S. District Attorney--who is very bitter--will hardly find twelve men so ignorant on the citizen's rights--as to agree on a verdict of Guilty." In May, however, Crowley convinced Judge Ward Hunt (the recently appointed justice of the U. S. Supreme Court who would hear Anthony's case) that Anthony had prejudiced potential jurors, and Hunt agreed to move the trial out of Monroe County to Canandaigua in Ontario County. Hunt set a new opening date for the trial of June 17.

Anthony responded to the judge's move by immediately launching a lecture tour in Ontario County. Anthony spoke for twenty-one days in a row, finally concluding her tour in Canandaigua, the county seat, on the night before the opening of her trial.

The Trial

Going into the June trial, Anthony and her lawyers were somewhat less optimistic about the outcome than they had been a few months before. In April, the U. S. Supreme Court handed down its first two major interpretations of the recently enacted Civil War Amendments, rejected the claimed violations in both cases and construing key provisions narrowly. Of special concern to Anthony was the Court's decision in Bradwell vs. Illinois, where the Court had narrowly interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause to uphold a state law that prohibited women from becoming lawyers. In an April 27 letter, Anthony anxiously sought out Benjamin Butler's views of the decision, noting that "The whole Democratic press is jubilant over this infamous interpretation of the amendments."

Courthouse at Canandaigua, N.Y., scene of the Anthony trial

Even without the Supreme Court's narrow interpretation of the amendments, many observers expressed skepticism about the strength of Anthony's case. An editorial in the New York Times concluded:

"Miss Anthony is not in the remotest degree likely to gain her case, nor if it were ever so desirable that women should vote, would hers be a good case. When so important a change in our Constitution as she proposes is made, it will be done openly and unmistakably, and not left to the subtle interpretation of a clause adopted for a wholly different purpose."

In a lengthy response to the Times editorial, Elizabeth Cady Stanton quoted Judge Selden as confidently telling Anthony, "there is law enough not only to protect you in the exercise of your right to vote, but to enfranchise every woman in the land."

On June 17, 1873, Anthony, wearing a new bonnet faced with blue silk and draped with a veil, walked up the steps of the Canandaigua courthouse on the opening day of her trial. The second-floor courtroom was filled to capacity. The spectators included a former president, Millard Fillmore, who had traveled over from Buffalo, where he practiced law. Judge Ward Hunt sat behind the bench, looking stolid in his black broadcloth and neck wound in a white neckcloth. Anthony described Hunt as "a small-brained, pale-faced, prim-looking man, enveloped in a faultless black suit and a snowy white tie."

Richard Crowley made the opening statement for the prosecution:

We think, on the part of the Government, that there is no question about it either one way or the other, neither a question of fact, nor a question of law, and that whatever Miss Anthony's intentions may have been-whether they were good or otherwise-she did not have a right to vote upon that question, and if she did vote without having a lawful right to vote, then there is no question but what she is guilty of violating a law of the United States in that behalf enacted by the Congress of the United States.

The prosecution's chief witness was Beverly W. Jones, a twenty-five-year-old inspector of elections. Jones testified that he witnessed Anthony cast a ballot on November 5 in Rochester's Eighth Ward. Jones added he accepted Anthony's completed ballot and placed it a ballot box. On cross-examination, Selden asked Jones if he had also been present when Anthony registered four days earlier, and whether objections to Anthony's registration had not been considered and rejected at that time. Jones agreed that was the case, and that Anthony's name had been added to the voting rolls.

The main factual argument that the defense hoped to present was that Anthony reasonably believed that she was entitled to vote, and therefore could not be guilty of the crime of "knowingly" casting an illegal vote. To support this argument, Henry Selden called himself as a witness to testify:

Before the last election, Miss Anthony called upon me for advice, upon the question whether she was or was not a legal voter. I examined the question, and gave her my opinion, unhesitatingly, that the laws and Constitution of the United States, authorized her to vote, as well as they authorize any man to vote.

Selden then called Anthony as a witness, so she might testify as to her vote and her state of mind on Election Day. District Attorney Crowley objected: "She is not a competent as a witness on her own behalf." Judge Hunt sustained the objection, barring Anthony from taking the stand. The defense rested.

The prosecution called to the stand John Pound, an Assistant United States Attorney who had attended a January examination in which Anthony testified about her registration and vote. Pound testified that Anthony testified at that time that she did not consult Selden until after registering to vote. Selden, after conferring with Anthony, agreed that their meeting took place immediately after her registration, rather than before as his own testimony had suggested. On cross-examination, Pound admitted that Anthony had testified at her examination that she had "not a particle" of doubt about her right as a citizen to vote. With Pound's dismissal from the stand, the evidence closed and the legal arguments began.

Selden opened his three-hour-long argument for Anthony by stressing that she was prosecuted purely on account of her gender:

If the same act had been done by her brother under the same circumstances, the act would have been not only innocent, but honorable and laudable; but having been done by a woman it is said to be a crime. The crime therefore consists not in the act done, but in the simple fact that the person doing it was a woman and not a man, I believe this is the first instance in which a woman has been arraigned in a criminal court, merely on account of her sex....

Selden stressed that the vote was essential to women receiving fair treatment from legislatures: "Much has been done, but much more remains to be done by women. If they had possessed the elective franchise, the reforms which have cost them a quarter of a century of labor would have been accomplished in a year."

Central to Selden's argument that Anthony cast a legal vote was the recently enacted Fourteenth Amendment:

It will be seen, therefore, that the whole subject, as to what should constitute the "privileges and immunities" of the citizen being left to the States, no question, such as we now present, could have arisen under the original constitution of the United States. But now, by the fourteenth amendment, the United States have not only declared what constitutes citizenship, both in the United States and in the several States, securing the rights of citizens to "all persons born or naturalized in the United States;" but have absolutely prohibited the States from making or enforcing " any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States." By virtue of this provision, I insist that the act of Miss Anthony in voting was lawful.

Finally, Selden insisted that even if the Fourteenth Amendment did not make Anthony's vote legal, she could not be prosecuted because she acted in the good faith belief that her vote was legal:

Miss Anthony believed, and was advised that she had a right to vote. She may also have been advised, as was clearly the fact, that the question as to her right could not be brought before the courts for trial, without her voting or offering to vote, and if either was criminal, the one was as much so as the other. Therefore she stands now arraigned as a criminal, for taking the only steps by which it was possible to bring the great constitutional question as to her right, before the tribunals of the country for adjudication. If for thus acting, in the most perfect good faith, with motives as pure and impulses as noble as any which can find place in your honor's breast in the administration of justice, she is by the laws of her country to be condemned as a criminal, she must abide the consequences. Her condemnation, however, under such circumstances, would only add another most weighty reason to those which I have already advanced, to show that women need the aid of the ballot for their protection.

After District Attorney Crowley offered his two-hour response for the prosecution, Judge Hunt drew from his pocket a paper and began reading an opinion that he had apparently prepared before the trial started. Hunt declared, "The Fourteenth Amendment gives no right to a woman to vote, and the voting by Miss Anthony was in violation of the law." The judge rejected Anthony's argument that her good faith precluded a finding that she "knowingly" cast an illegal vote: "Assuming that Miss Anthony believed she had a right to vote, that fact constitutes no defense if in truth she had not the right. She voluntarily gave a vote which was illegal, and thus is subject to the penalty of the law." Hunt then surprised Anthony and her attorney by directing a verdict of guilty: "Upon this evidence I suppose there is no question for the jury and that the jury should be directed to find a verdict of guilty."

In her diary that night Anthony would angrily describe the trial as "the greatest judicial outrage history has ever recorded! We were convicted before we had a hearing and the trial was a mere farce." During the entire trial, as Henry Selden pointed out, "No juror spoke a word during the trial, from the time they were impaneled to the time they were discharged." Had the jurors had an opportunity to speak, there is reason to believe that Anthony would not have been convicted. A newspaper quoted one juror as saying, "Could I have spoken, I should have answered 'not guilty,' and the men in the jury box would have sustained me."

Sentencing

The next day Selden argued for a new trial on the ground that Anthony's constitutional right to a trial by jury had been violated. Judge Hunt promptly denied the motion. Then, before sentencing, Hunt asked, "Has the prisoner anything to say why sentence shall not be pronounced?" The exchange that followed stunned the crowd in the Canandaigua courthouse:

"Yes, your honor, I have many things to say; for in your ordered verdict of guilty, you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored. Robbed of the fundamental privilege of citizenship, I am degraded from the status of a citizen to that of a subject; and not only myself individually, but all of my sex, are, by your honor's verdict, doomed to political subjection under this, so-called, form of government."

Justice Ward Hunt

Judge Hunt interrupted, "The Court cannot listen to a rehearsal of arguments the prisoner's counsel has already consumed three hours in presenting."

But Anthony would not be deterred. She continued, "May it please your honor, I am not arguing the question, but simply stating the reasons why sentence cannot, in justice, be pronounced against me. Your denial of my citizen's right to vote, is the denial of my right of consent as one of the governed, the denial of my right of representation as one of the taxed, the denial of my right to a trial by a jury of my peers as an offender against law, therefore, the denial of my sacred rights to life, liberty, property and-"

"The Court cannot allow the prisoner to go on."

"But your honor will not deny me this one and only poor privilege of protest against this high-handed outrage upon my citizen's rights. May it please the Court to remember that since the day of my arrest last November, this is the first time that either myself or any person of my disfranchised class has been allowed a word of defense before judge or jury-"

"The prisoner must sit down-the Court cannot allow it."

"All of my prosecutors, from the eighth ward corner grocery politician, who entered the compliant, to the United States Marshal, Commissioner, District Attorney, District Judge, your honor on the bench, not one is my peer, but each and all are my political sovereigns; and had your honor submitted my case to the jury, as was clearly your duty, even then I should have had just cause of protest, for not one of those men was my peer; but, native or foreign born, white or black, rich or poor, educated or ignorant, awake or asleep, sober or drunk, each and every man of them was my political superior; hence, in no sense, my peer. Even, under such circumstances, a commoner of England, tried before a jury of Lords, would have far less cause to complain than should I, a woman, tried before a jury of men. Even my counsel, the Hon. Henry R. Selden, who has argued my cause so ably, so earnestly, so unanswerably before your honor, is my political sovereign. Precisely as no disfranchised person is entitled to sit upon a jury, and no woman is entitled to the franchise, so, none but a regularly admitted lawyer is allowed to practice in the courts, and no woman can gain admission to the bar-hence, jury, judge, counsel, must all be of the superior class.

"The Court must insist-the prisoner has been tried according to the established forms of law."

"Yes, your honor, but by forms of law all made by men, interpreted by men, administered by men, in favor of men, and against women; and hence, your honor's ordered verdict of guilty; against a United States citizen for the exercise of "that citizen's right to vote," simply because that citizen was a woman and not a man. But, yesterday, the same man made forms of law, declared it a crime punishable with $1,000 fine and six months imprisonment, for you, or me, or you of us, to give a cup of cold water, a crust of bread, or a night's shelter to a panting fugitive as he was tracking his way to Canada. And every man or woman in whose veins coursed a drop of human sympathy violated that wicked law, reckless of consequences, and was justified in so doing. As then, the slaves who got their freedom must take it over, or under, or through the unjust forms of law, precisely so, now, must women, to get their right to a voice in this government, take it; and I have taken mine, and mean to take it at every possible opportunity."

"The Court orders the prisoner to sit down. It will not allow another word."

"When I was brought before your honor for trial, I hoped for a broad and liberal interpretation of the Constitution and its recent amendments, that should declare...equality of rights the national guarantee to all persons born or naturalized in the United States. But failing to get this justice-failing, even, to get a trial by a jury not of my peers-I ask not leniency at your hands-but rather the full rigors of the law--"

"The Court must insist-"

Finally, Anthony sat down, only to be immediately ordered by Judge Hunt to rise again. Hunt pronounced sentence: "The sentence of the Court is that you pay a fine of one hundred dollars and the costs of the prosecution."

Anthony protested. "May it please your honor, I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty. All the stock in trade I possess is a $10,000 debt, incurred by publishing my paper- The Revolution -four years ago, the sole object of which was to educate all women to do precisely as I have done, rebel against your manmade, unjust, unconstitutional forms of law, that tax, fine, imprison and hang women, while they deny them the right of representation in the government; and I shall work on with might and main to pay every dollar of that honest debt, but not a penny shall go to this unjust claim. And I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, that "Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God."

Judge Hunt, in a move calculated to preclude any appeal to a higher court, ended the trial by announcing, "Madam, the Court will not order you committed until the fine is paid."

Epilogue

True to her word, Anthony never paid a penny of her fine. Her petition to Congress to remit the fine was never acted upon, but no serious effort was ever made by the government to collect.

Anthony tried to turn her trial and conviction into political gains for the women suffrage movement. She ordered 3,000 copies of the trial proceedings printed and distributed them to political activists, politicians, and libraries. In the eyes of some, the trial had elevated Anthony to the status of the martyr, while for others the effect may have been to diminish her status to that of a common criminal.

In the eyes of some, the trial elevated Anthony to the status of the martyr. While for others, the effect may have been to diminish her status to that of a common criminal. Many in the press, however, saw Anthony as the ultimate victor. One New York paper observed, "If it is a mere question of who got the best of it, Miss Anthony is still ahead. She has voted and the American constitution has survived the shock. Fining her one hundred dollars does not rule out the fact that...women voted, and went home, and the world jogged on as before."

About 150 women overall attempted to vote in 1872. One woman who tried and failed was Virginia Minor of St. Louis. After she was turned away, she sued the register, Reese Happersett. Three years later, the case of Minor v Happersett reached the US Supreme Court. The result was not what Minor, or Anthony, hoped. The Court ruled that citizenship under the 14th Amendment meant “membership in a nation and nothing more.”

Minor v Happersett would be the law for nearly a half a century until ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.