CHAPTER IV.

THE ATTEMPT TO PURCHASE BURNS (by Charles Emery Stevens, 1856)

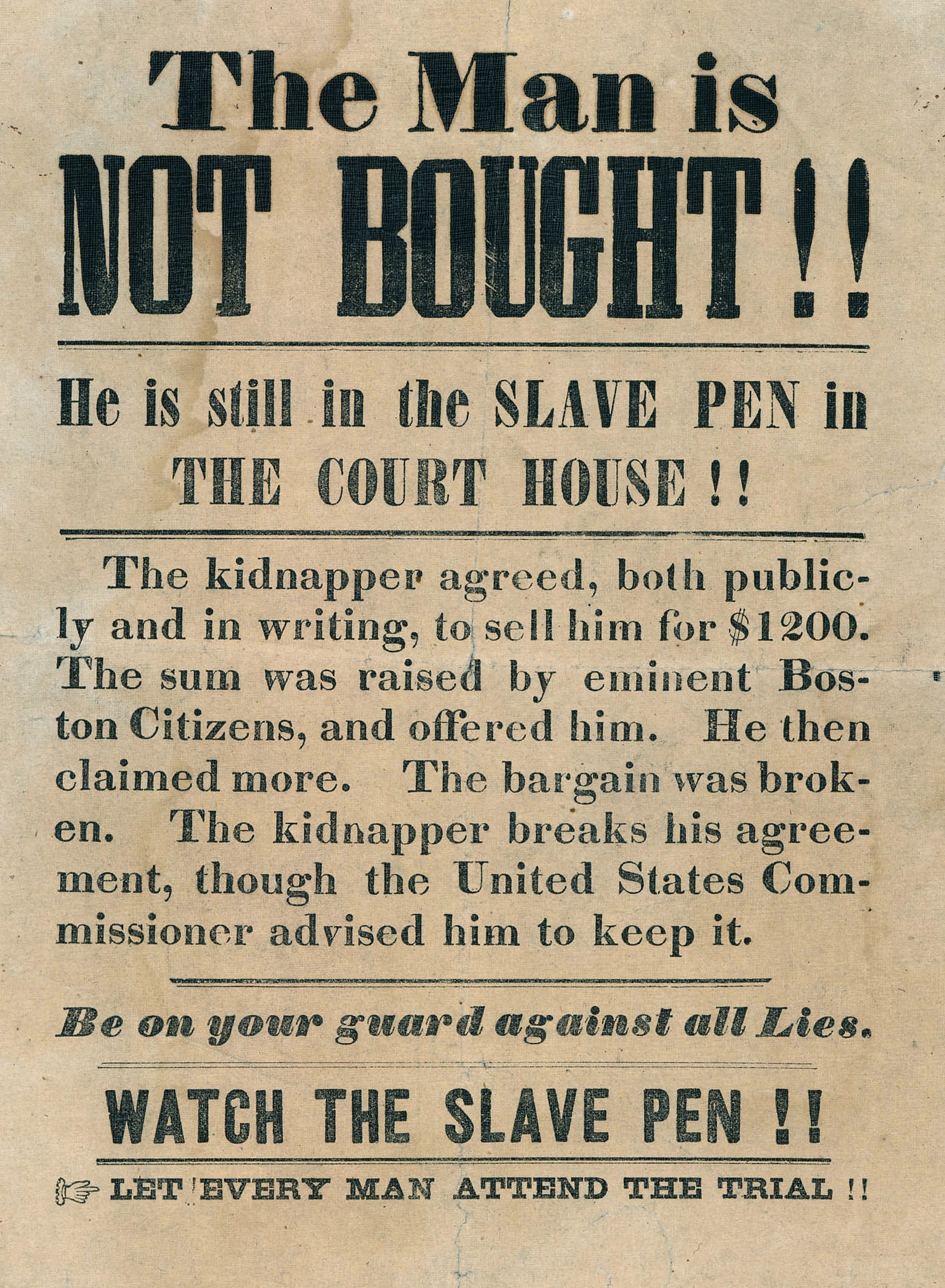

THE rising anger of the people filled the claimant's counsel with dismay. They feared for their own personal safety. They went constantly armed; one of them even attempted a sort of disguise. Avoiding the thronged thoroughfares, they stole to and from the Court House through the most unfrequented streets. The attack on the Court House, with the death of Batchelder, wrought their fears to a still higher pitch. It showed them that there was a band of men ready for the most desperate service that might be necessary. It prophesied fearfully of the future. What would ensue if the fugitive were surrendered? Surrendered, they at least were well assured he would be. Foreseeing this result, and taking counsel of their fears, they now resolved to avert the threatening tempest by offering Burns for sale. Thus, it was with Col. Suttle and his advisers that this proposal originated.1

1 Colonel Suttle, despite the endorsement of his courage by Virginia, implied in his military title, appears to have been thrown into a state of extreme terror by the angry demonstrations which he had provoked. For greater personal security, he changed his quarters, in the Revere House, from a lower story to the attic, barricaded his door at night, and kept under pay four armed men to lodge with him in the room and guard him from danger. The demonstrations which so excited his fears, proceeded chiefly from the colored men of the city. For example, four or five powerful fellows maintained an unceasing watch on a street corner, which commanded a view of his window, and never left the spot while he was known to be in the house, except to give place to a fresh set. It was afterward confessed that this expedient was adopted merely to intimidate the Colonel, and it seems to have been quite successful.

Page 62

The first announcement of this purpose was made in open court on Saturday morning. The counsel for Burns had moved for a postponement of the examination, for the purpose of gaining a little time to prepare the defence. To this the counsel for Suttle objected.

"Let the examination proceed now," said one of them, Edward G. Parker, "and if Burns is given up, I am authorized to say that he can be purchased."

Among those who heard this statement, was one who had already done and suffered much in behalf of fugitive slaves. This man was the Rev. L. A. Grimes, the pastor of a congregation of colored persons in Boston. Approaching the counsel, Mr. Grimes inquired upon what authority the statement had been made. "Col. Suttle has agreed to sell Burns," was the reply. Mr. Parker added that the sum which he had agreed to accept was twelve hundred dollars. But a condition annexed was, that the sale should be made after the surrender had been decreed. Mr. Grimes inquired if Col. Suttle would not consent to receive the sum named and close a bargain before the surrender. The counsel thought not. Bent on securing this concession,

Page 63

Mr. Grimes sought an interview with the Marshal, by whom, on mentioning his object, he was referred to Col. Suttle. An introduction of the slave-rescuer to the slave-hunter took place, and a long conversation ensued. Suttle enlarged on the fact of his ownership, on the kindness with which he had treated Burns, and also on the latter's good character. But to all suggestions for a sale before the surrender, he refused to listen. A private interview between Suttle and his counsel followed. At the close of it, the latter sought Mr. Grimes and informed him that their client had at length agreed to sell his slave before the surrender was made. The prompt response of Mr. Grimes was--"Between this time and ten o'clock to-night, I'll have the money ready for you; have the emancipation papers ready for me at that hour."

A busy day's work lay before the benevolent pastor. The morning was already well advanced, and before the day closed, twelve hundred dollars were to be raised, not one of which had yet been subscribed, Without resources himself, he had to seek out others who might be disposed to contribute to the enterprise. A wealthy citizen, whose sympathies had hitherto been on the side of the fugitive slave act, had been heard to say that if Burns could be purchased he would head the subscription list with a hundred dollars. Informed of this by Suttle's counsel, Mr. Grimes called at the gentleman's house, and on the third attempt succeeded in finding him. The gentleman admitted

Page 64

that he had made the pledge already mentioned, but he now declined to redeem it. He had since met a person, he said, who had assured him that the slave could not be purchased,--that he must be tried.

"I have heard no one take that ground but the United States District Attorney," said Mr. Grimes.

The gentleman confessed that it was Attorney Hallett who had dissuaded him from acting upon his benevolent impulse. Without money, but with a promise from him to give "something," which was never redeemed, Mr. Grimes left the house.

He now bent his steps toward the mansion of a gentleman distinguished for his immense wealth, his rare munificence, and the eminent position which he had formerly held in the service of his country abroad. Everything conspired to ally him with the conservative class of society, and it was with them that public opinion commonly ranked him. What view he would take of the passing events was uncertain. Mr. Grimes found him in an unusually discomposed frame of mind. The announcement of his errand at once called forth an emphatic expression of sentiment and feeling. He denounced the fugitive slave act as "an infamous statute," and declared that he would have nothing to do with it. It had been the cause of bloodshed and slaughter, and would be the cause of still more. Referring to the death of Batchelder, he intimated that, as the man had been killed while voluntarily assisting to execute an infamous law,

Page 65

he had no regrets to express at the occurrence. He could give no money to purchase the freedom of Burns, as that, in his view, would be an implied sanction of the law; but, if Mr. Grimes needed any money for his own uses, he might draw on him for the required sum, or even for a larger amount.1

1 The above was written while ABBOTT LAWRENCE was yet living. Now that death has set his seal on all his acts and opinions, I need no longer hesitate to name him as the person alluded to. Let the sentiments expressed in the text go forth to the public under the sanction of such a name.

Thus encouraged, Mr. Grimes took his leave.

A gentleman belonging to a family distinguished for its ability, and especially for its devotion to the fugitive slave law, was next applied to. At once intimating his readiness to contribute to the proposed purchase, he suggested that his brother, a wealthy merchant, should be summoned for the same purpose. The latter soon made his appearance and entered heartily into the scheme. Each subscribed one hundred dollars on condition that the whole sum should be raised. Both were urgent in pressing forward the matter; "the man," said one of them, "must be out of the Court House tonight." If the sum should not be made up, he was ready to increase his subscription. From another distinguished citizen the sum of fifty dollars was obtained; he was the only member of the national legislature from Massachusetts who had perilled his reputation by voting for the fugitive slave bill. A subscription was next solicited

Page 66

from a certain rich broker in State street. He had been an ardent supporter of the fugitive act; on the occasion of sending Sims back into slavery he had offered five thousand dollars, if need were, to secure that triumph. Mr. Grimes now found him in a different mood. He would give nothing to purchase Burns--there would be no end to demands of that sort; but he would readily contribute one hundred dollars, he said, to procure a coat of tar and feathers for the slave-catchers. Apparently, his patriotism cost him nothing on either occasion. Another millionaire of the city, who enjoyed a reputation for liberality, upon being solicited to subscribe, declined on the ground that it would only furnish an inducement for slaveholders to repeat their reclamations. At the same time, he declaimed with great bitterness against the law.

Hamilton Willis, a broker in State street, responded to the call with the most active sympathy. He urged Mr. Grimes to obtain pledges for the necessary amount, and agreed to advance the money upon those pledges. Another noble contributor was one who, as a Trustee of the Emigrant Aid Society, afterward distinguished himself in peopling Kansas with freemen. This was J. M. S. Williams, a native of Virginia, but then a merchant in Boston. Subscribing at once a hundred dollars, he gave assurance that whatever sum might be deficient in the end, he would make good.

Page 67

Smaller amounts were subscribed by various other persons.

At seven o'clock in the evening, Mr. Grimes had obtained pledges for eight hundred dollars. Repairing to the office of the United States Marshal, he there, according to appointment, met Mr. Willis. The latter at once filled up his cheque for the eight hundred dollars and placed it in the hands of the Marshal, to be applied toward the purchase of Burns. The counsel of Suttle had also agreed to meet Mr. Grimes at the same time and place, but they failed to make their appearance. The truth was, that, in the excess of their anxiety to have the purchase of Burns effected, one of them had undertaken to solicit subscriptions himself, and was still absent on that business.

Again Mr. Grimes went forth,--this time in company with a well known philanthropist,--and several hours were spent in fruitless endavors to make up the required amount. Late in the evening, they drove to the Revere House, where Col. Suttle had taken rooms. Soon after, the two gentlemen who acted as his counsel arrived there also. One of them now informed Mr. Grimes that he had called on the two brothers already spoken of as being so eager for the purchase of Burns, from one of whom he had received a cheque for four hundred dollars additional to his previous subscription. This was a temporary advance, however, made for the purpose of consummating the transaction within the time prescribed by Col. Suttle,

Page 68

and to be refunded on the following Monday. The required sum was thus completed, and nothing remained but to execute the bill of sale.

It was now half-past ten o'clock. Another half hour was consumed by a private interview between Suttle and his counsel. The several parties then separated to meet immediately after, at the private office of Commissioner Loring, with whom one of Suttle's counsel had already made an arrangement to draw up the instrument of sale. The Commissioner soon made his appearance, and at once proceeded to write a bill of sale, in these words:

"Know all men by these presents, that I, Charles F. Suttle, of Alexandria in Virginia, in consideration of twelve hundred dollars to me paid, do hereby release and discharge, quitclaim and convey to Antony Byrne1

1 The name has been variously spelt; as the slave of Col. Suttle he was probably known by the name given in the bill of sale. But by his baptism of suffering he took the name of Anthony Burns, and under that designation entered upon his new life of freedom.

his liberty; and I hereby manumit and release him from all claims and service to me forever, hereby giving him his liberty to all, intents and effects forever. In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal, this twenty-seventh day of May, in the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and fifty-four."

Having completed this instrument, the Commissioner sent a messenger to Marshal Freeman, requesting his attendance at the office of the former. The Marshal declined to comply with this request.

Page 69

Mr. Loring then gathered up his papers, and, with the other parties, proceeded to the Marshal's office, where they found that official in company with District Attorney Hallett. He at once began to confer with the Marshal concerning the purchase of Burns, when Hallett interposed and strenuously objected to the transaction. He maintained that if Burns were, by purchase, taken out of the hands of the United States officers, before the examination were concluded, nobody would be responsible for the expenses already incurred; and he took it upon him to add that the Government would not defray them. To this the Commissioner replied by reading a portion of the fugitive slave act. That, he contended, made the Government responsible for the expenses; by the sale, Suttle would obtain an equivalent for his slave, and thus the law would be substantially enforced. This absurd objection having been thus silenced, the District Attorney was ready with another. There was, he said, an existing law of Massachusetts, which prohibited such a transaction. The Commissioner promptly replied that the law referred to was not applicable to the case in hand; that it was a law aimed not against selling a man into freedom, but against selling him into slavery.1

1 The statute referred to, I presume, was this: "Every person who shall sell, or in any manner transfer for any term, the service or labor of any negro, mulatto, or other Person of unlawfully seized color who shall have been taken, inveigled, or kidnapped from this State to any other State, place, or country, shall be Punished by imprisonment in the State Prison not more than ten years, or by a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars and imprisonment in the county jail not more than two years."--Revised Statutes of Massachusetts, Chap. 125, Sec. 20.

As Mr. Hallett was not

Page 70

required to be a party to the transaction, his concern on this point seemed to be somewhat gratuitous. Failing to produce conviction by arguments of this character, as a last resort he urged that the sale, if effected then, would not be legal, as the Sabbath had already commenced. Glancing toward the clock, the Commissioner saw that the minute-hand pointed to a quarter past twelve. He ceased to urge the point further, and, turning to Mr. Grimes, said: "It can be done at eight o'clock on Monday morning--come to my office then, and it can be settled in five minutes." The negotiations were then broken off.

Mr. Grimes turned away in deep disappointment. So confident was he of success, that he had a carriage in waiting at the door of the Court House to bear Burns away as a freeman. The prisoner had been apprised of the movement in his behalf, and with feverish intent was momently waiting for his release. Mr. Grimes now asked permission to communicate to him the result of the negotiations, and thus relieve him of a most painful suspense; but the Marshal refused his consent, at the same time charging himself with the duty.

As the Sabbath wore on, rumors spread through the city that dispatches unfavorable to the release of the prisoner had been received from the Federal

Page 71

Government. Full of fears, Mr. Grimes sought an interview, at evening, with the Commissioner, at his private residence. The latter endeavored to re-assure him. Col. Suttle, he still felt confident, would abide by his agreement. "But if he fails to," said the Commissioner, "and the counsel for the defence can raise a single doubt, Burns shall walk out of the Court House a free man." He closed the interview by renewing the appointment to meet at eight o'clock, the next morning, for completing the purchase.

Punctual at the hour, Mr. Grimes repaired to the Commissioner's office, but the latter failed to appear. After waiting an hour, he went in pursuit of the delinquent functionary, but without success. He then sought Col. Suttle and his counsel at the Revere House; they were not there. At length he found them, together with Brent, Hallett, and the Marshal, assembled in the office of the latter. Reminding them of the appointment they had broken, he announced his readiness to complete the contract which had already been verbally made. Then Col. Suttle proceeded to vindicate his Virginian honor. As the bargain had not been completed on Saturday night, he said he should now decline to sell Burns; the trial must go on.

"After Burns gets back to Virginia," he graciously added, "you can then have him."

In vain Mr. Grimes urged that the failure on Saturday night occurred through no fault of his. Mr. Hallett here interrupted him.

Page 72

"No," said he, "when Burns has been tried and carried back to Virginia and the law executed, you can buy him; and then I will pay one hundred dollars towards his purchase."

Mr. Grimes insisted that by agreement the man was already his. The District Attorney then said:

"The laws of the land cannot be trampled upon. A man has been killed; that blood"--pointing to the spot in the Marshal's office where Batchelder had breathed his last--"must be atoned for." Mr. Hallett thus assumed a responsibility from which he afterward, through the public press, vainly endeavored to escape.

Baffled and despondent, Mr. Grimes turned away and sought those who had subscribed to the purchase fund. He first met that supporter of the fugitive slave act who had manifested such anxiety for the release of Burns on Saturday, and who had subscribed a hundred dollars. "If the man is to be tried," said this subscriber, "I refuse to give a cent for his purchase; I would rather give five hundred dollars than have the trial go on." It was not the well-being of the slave that he sought; it was to save Boston from the ignominy arising from the execution of the fugitive slave act. Other subscribers took substantially the same position, and thus the subscription fell to the ground. Some further attempts to effect the purchase were made, in which the philanthropic broker, Mr. Willis, bore the principal share. The story of his efforts and their result is best given in his own words.

Page 73

"Tuesday morning," he writes, "I had an interview with Col. Suttle in the United States Marshal's office. He seemed disposed to listen to me, and met the subject in a manly way. He said he wished to take the boy [Burns] back, after which he would sell him. He wanted to see the result of the trial at any rate. I stated to him that we considered his claim to Burns clear enough, and that he would be delivered over to him, urging particularly upon him that the boy's liberation was not sought for except with his free consent, and his claim being fully satisfied. I urged upon him no consideration of the fear of a rescue, or possible unfavorable result of the trial to him, but offered distinctly, if he chose, to have the trial proceed, and whatever might be the result, still to satisfy his claim. I stated to him that the negotiation was not sustained by any society or association whatsoever, but that it was done by some of our most respectable citizens, who were desirous not to obstruct the operation of the law, but in a peaceable and honorable manner sought an adjustment of this unpleasant case; assuring him that this feeling was general among the people. I read to him a letter addressed to me by a highly esteemed citizen, urging me to renew my efforts to accomplish this, and placing at my disposal any amount of money that I might deem necessary for the purpose.

"Col. Suttle replied that he appreciated our motives, and that he felt disposed to meet us. He then stated what he would do. I accepted his

Page 74

proposal at once; it was not entirely satisfactory to me, but yet, in view of his position as he declared to me, I was content. At my request, he was about to commit our agreement to writing, when Mr. B. F. Hallett entered the office, and they two engaged in conversation apart from me. Presently Col. Suttle returned to me, and said 'I must withdraw what I have done with you.' We both immediately approached Mr. Hallett, who said, pointing to the spot where Mr. Batchelder fell, in sight of which we stood,--'That blood must be avenged.' I made some pertinent reply, rebuking so extraordinary a speech, and left the room.

"On Friday (June 2d), soon after the decision had been rendered, finding Col. Suttle had gone on board the cutter [which was to carry Burns back to Virginia] at an early hour, I waited upon his counsel at the Court House, and there renewed my proposition. Both these gentlemen promptly interested themselves in my purpose, which was to tender the claimant full satisfaction, and receive the surrender of Burns from him, either there, in State street, or on board the revenue cutter, at his own option. It was arranged between us that Mr. Parker [junior counsel for Suttle] should go at once on board the cutter and make an arrangement if possible, with the Colonel. I provided ample funds, and returned immediately to the Court House, when I found that there would be difficulty in getting on board the cutter. Application

Page 75

was made by me to the Marshal; he interposed no objection, and I offered to place Mr. Parker alongside the vessel. Presently Mr. Parker took me aside, and said these words: 'Col. Suttle has pledged himself to Mr. Hallett that he will not sell his boy until he gets him home.' Thus the matter ended."1

1 Letter of Hamilton Willis, addressed to the Editors of the Boston Atlas and Published in that journal, June 5,1854, in reply to Mr. Hallett's public denial of the charge that he had interfered to Prevent the purchase of Burns.

When Burns was fairly out to sea, on his way back to Virginia, and beyond the reach of immediate aid, the officers of the division of Massachusetts militia that had assisted in enforcing his rendition, also made an effort toward procuring his emancipation. Assembling at one of their ward houses, they formally organized themselves into a meeting, and unanimously raised a committee to obtain funds for the purchase of Burns. Their purpose took a still more definite shape: jealous for the honor of their military body, they voted that the subscription should be strictly confined to the officers and members of their division. Unhappily, this was the end, as well as the beginning, of their efforts. The cause of the failure, as afterwards assigned by some of their number, was the severe criticism with which their participation in the surrender had been treated by the public press. Finding that the proposed benefaction was not likely to efface from the public mind the remembrance

Page 76

of their previous official conduct, they abandoned their purpose and prudently reserved their money.

In time, news reached Boston that Burns had arrived in Virginia. The law had been executed, the point of honor had been satisfied, Slavery had its own again. Negotiations were once more renewed. At the request of Mr. Grimes, Mr. Willis addressed a letter to Col. Suttle on the subject. The reply of the latter is entitled to a place in this history.

"I have had much difficulty in my own mind," he writes, "as to the course I ought to pursue about the sale of my man, Anthony Burns, to the North. Such a sale is objected to strongly by my friends, and by the people of Virginia generally, upon the ground of its pernicious character, inviting our negroes to attempt their escape under the assurance that, if arrested and remanded, still the money would be raised to purchase their freedom. As a southern man and a slave-owner, I feel the force of this objection and clearly see the mischief that may result from disregarding it. Still, I feel no little attachment to Anthony, which his late elopement, [with] the vexation and expense to which I have been put, has not removed; and I confess to some disposition to see the experiment tried of bettering his condition.

"I understand the application now made to purchase his freedom, does not come from the abolitionists and incendiaries who put the laws of

Page 77

the Union at defiance, and dyed their hands in the blood of Batchelder, but from those who struggled to maintain law and order.

"Now that the laws have been fully vindicated (although at the point of the bayonet) and Anthony returned to the city of Richmond, from which he escaped; and believing that it would materially strengthen the Federal Officers and facilitate the execution of the laws in any future case which might arise, and influenced by other considerations to which I have referred, I have concluded to sell him his freedom for the sum of fifteen hundred dollars.

"When in Boston, acting under the extraordinary counsel of Mr. Parker, one of my lawyers, I agreed to take twelve hundred dollars if paid at a fixed period. The money was not forthcoming at the time agreed upon,1

1 This was not true, as the narrative in the former part of this chapter shows.

and I then, being better advised, determined the law should take its course.

"By the course pursued of violent, corrupt, and perjured opposition to my rights, the case was protracted for days after my offer to take twelve hundred dollars; consequently my expenses were generally increased, I presume materially so to my attorneys, to whom I paid from my private purse four hundred dollars.2

2 The excuse which Col. Suttle here presents for his exorbitant demand for Burns will hardly stand a severe scrutiny. According to his own admission, he had agreed to accept twelve hundred dollars. Afterward, acting under "better advice," he withdrew his offer for the purpose of letting the law take its course. The law did take its course, and an increase of his expenses was the natural result. The proposed purchasers were anxious to have him take a step that would diminish his expenses; he insisted on pursuing a course which he knew would increase them, and then, because they were increased, required that the purchasers should bear the burden. It furnishes some relief to one's sense of justice to know that he was afterwards obliged to go farther and fare worse.

Page 78

"Now, as I am not a man of wealth, and I am bound to have a moderate regard for my private interest, it will readily be seen that twelve hundred dollars at the time I agreed to take it, would have been better for me than fifteen hundred now.

"In reply to your question about his (Burns,) character, I have to say that I regard him as strictly honest, sober, and truthful. Let me hear from you without delay. If you accede to my terms, I will, on receipt of the money, deliver him in the city of Washington with his free papers, or I will send him by one of the steamers from Richmond to New York."

With this new proposition, the indefatigable pastor, Grimes, sought first of all Mr. Hallett, and, informing him of its nature, plainly told the attorney that, as he was the only one who had hindered the purchase of Burns at twelve hundred dollars, he alone ought to bear the burden of the excess now demanded over that sum. Hallett refused to grace himself by such an act of justice, but, nevertheless, declared his willingness to give a hundred dollars toward the sum required. Col. Suttle's proposition was next laid before the persons who had acted as

Page 79

his counsel. They addressed a letter to him, declaring it as their opinion that he was bound to accept twelve hundred dollars for Burns ; but nothing came of this remonstrance. Mr. Grimes then applied to the original subscribers to the twelve hundred dollar fund. Most of them were ready to renew their pledges, provided Burns could be purchased for that amount; but they absolutely refused to give anything if a higher sum were insisted on. Col. Suttle was then informed by Mr. Grimes that he could still have the twelve hundred dollars, but nothing more. To this no answer was ever returned, and for the time all efforts to ransom Burns were at an end.