Jack Kevorkian Decides to Represent Himself (March 22, 1999)

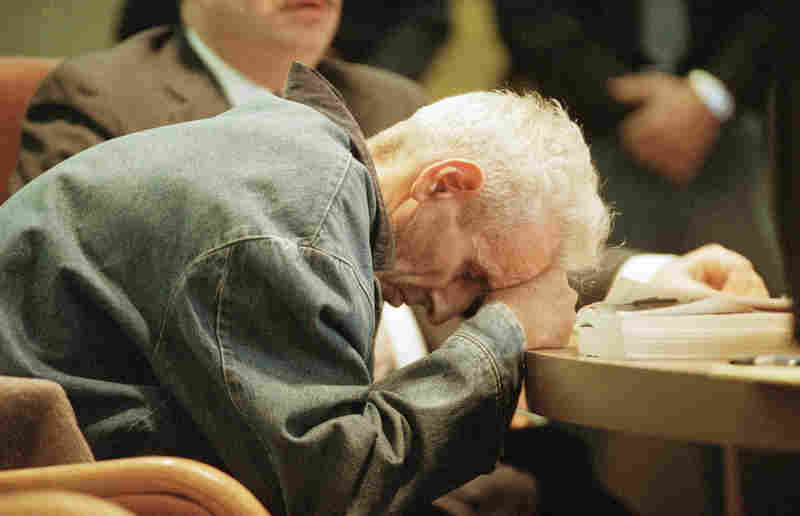

JACK KEVORKIAN DURING HIS MARCH 1999 TRIAL

For the first day of the Youk trial, Jack Kevorkian was represented by counsel. But then Kevorkian told judge Jessica Cooper that he wished to represent himself for the duration of the trial. What follows is the exchange between Kevorkian and Judge Cooper on that decision--the decision that cost him any real chance of avoiding conviction.

The Court: And do you have any reason for this dissatisfaction [with your lawyers]?

[Defendant ]: There's no dissatisfaction. This is what I planned all along.

The Court: You planned all along to represent yourself?

[Defendant ]: To represent myself, yes.

The Court: And so you have no independent dissatisfaction with your attorney?

[Defendant ]: None.

After clearing up this point, the trial court explained to defendant that he could spend the rest of his life in prison and that a criminal trial is a formal, complex, and dynamic proceeding. Further, the trial court noted, the rules of evidence applied, as well as “certain decorum and certain ways in which there are presentations made to the jury and certain things that you can say and you can't say.” The trial court asked defendant whether there was a specific reason that he wished to represent himself and he answered, “Yes.”

The Court: What is that, sir?

[Defendant ]: There are certain points I could bring out better than any attorney. Certain questions I can ask that are more pertinent.

The trial court informed defendant that, with respect to jury selection, opening statements, and closing statements, he would be bound by the rules of the court and that there would be a permanent record that might be used in other proceedings. The trial court stated that counsel could be present at the table with defendant in order to consult with, but that such advisors “can't get up and speak.”

[Defendant ]: No, I said as advisors, consultation and advice. That's what I meant.

The Court: And that's what you wish to do?

[Defendant ]: Yes.

The Court: You're aware of all of these dangers?

[Defendant ]: Very much so.

The Court: You understand we're talking about something that could carry a sentence of life imprisonment without any possibility of parole?

[Defendant ]: Yes.

The Court: And do you understand that you may not disrupt or inconvenience the Court?

[Defendant ]: I'm here by my own invitation. I'll act like the guest I am.

The Court: And that means you will follow my orders and procedures?

[Defendant ]: As a guest.

The Court: Well, it's more than a guest. You're here as a defendant, sir.

[Defendant ]: But as a guest, propriety will be observed.

The Court: Has anyone promised you or threatened you in any way that makes you want to do this?

[Defendant ]: No, not at all. It's my own free will.

In light of this exchange, the trial court determined that defendant had unequivocally, knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily waived his right to counsel. Defendant then represented himself during jury voir dire and gave his own opening statement.

On March 23, 1999, the second day of trial, before any witnesses were presented, the trial court again asked defendant if he still wished to proceed in propria persona. Defendant indicated that he still wished to represent himself, and did so by examining and cross-examining the witnesses. During a conference on the record in chambers on that day, the trial court again pointed out the difficulties of self-representation, to which defendant replied:

I don't want you to agonize, I really don't. Do what you know is right, do it forcefully and definitely. It won't offend me and if you think I'm making mistakes or I don't know what I'm doing, I'll do the best I can with my advisers here. I made this choice. I don't blame anybody else, and I don't want you to agonize over it. And I don't want you to jeopardize your position.

The trial court again raised the specter of punishment with defendant:

The Court: ․ I just want you to understand that if you're convicted of this offense it's the rest of your life.

[Defendant ]: I go to jail. I go to jail, yes. I go to jail.

The Court: Mandatory.

[Defendant ]: If I'm convicted, Your Honor, we get a shot at the Supreme Court. Not that they'll accept it, but we get a shot at it with what they want, a particularized case. They said that, we got their quotes. They want a particularized case. Four of them said we want to revisit this issue again. Now two or three years may be too quick, but when you've got someone starving to death in prison who you know is not a criminal and you know what he's doing is not a crime, maybe they'll look at it-maybe.

But if not, who cares. In 15, 20 years, they'll say well, he was right. He's dead now, but he was right. I've got to do what I know now is right and I can't let the law, which is often immoral, block me. If Margaret Sanger did that, if Susan B. Anthony did that-look at Martin-look at all these people. I'm not saying I'm like them, but they certainly-I'm certainly going to act like them. I mean, I know this is not a crime. So do you. Everybody with sense does. Your religion may say it's a sin, but that doesn't make it a crime. All these people broke the law and went to jail. I am willing to do the same.

But the Supreme Court has got to decide this on the Ninth Amendment where there is no equivocation, there is no stretching due process. They've got to do that. And if they do and break all these laws down, then we can have a better society, an honest society. I'm willing to risk that. Because at age of 71, I cannot go on living a hypocritical life when I can't do what I know is right, and the world knows I'm right. Everybody does. Every nation the majority is for what I'm doing. How come it's illegal? That's why I'm doing this.

On March 25, 1999, the third day of trial, defendant rested and gave his closing argument, during which he stated several times that he was acting as his own attorney. The trial court instructed the jury that defendant had a constitutional right to represent himself and that they, the jurors, must not give any negative consideration to defendant's decision to do so.