Two dramatic criminal trials, one for rape and one for murder and both involving multiple defendants, forever changed the nature of Hawaiian race relations and politics. Filled with twists and turns and unanswered questions, the trials have all the elements of a good mystery. The second of the so-called "Massie Affair" trials also closes out the courtroom career of America's greatest defense attorney, Clarence Darrow. No trials ever had a more significant effect on a state's history than those that shocked and shook Hawaii in 1931 and 1932.

An Allegation of Rape

Thalia Massie

The plan was to spend the evening of Saturday September 12, 1931 at a nightclub on the outskirts of Honolulu's Waikiki district. Thalia Massie, with a blueblood background and a belief in her own sophistication, was much less enthusiastic about the prospect than her husband of four years, naval officer Thomas Massie. She anticipated the night would include another night of heavy drinking for Tommie and his submarine buddies. Her marriage, however, was on the rocks. She decided that joining the party beat the alternatives. After an hour of chatting over bootleg liquor with two other officers and their wives, the Massies left their bungalow in the Manoa Valley about 9:30. They pulled up in their Model A Ford in front of the two-story Ala Wai Inn, a framed building advertised as having "the largest open-air pavilion in Honolulu." Saturday night was dubbed Navy night--fifty cents bought four hours of dancing until 1:00 a.m.

Around 11:30, Thalia was in an upstairs room, agitated over the fact that Tommie had spent most of the previous two hours ignoring her. She slipped into the seat of a drunken submarine skipper who had left for the bathroom. When the skipper returned, he demanded his seat back. Thalia refused, the skipper called her a "louse," and she responded with a hard slap to his face. Tommie was called to calm down his wife. It was just before midnight. Thalia, bored with the party, left the Ala Wai Inn and began walking down Kalakaua Avenue in the direction of the beach. Tommie, assuming that Thalia had found her own way home, hung around the Inn until the party ended.

Shortly before 1:00 a.m., Thalia Massie flagged down a car on Ala Moana Road. The passengers turned out to be two middle-aged couples and the son of one the couples, all on their way to a late night eatery. One of the passengers, Mrs. George Clark, recalled later that Thalia had a "badly swollen" face and lips and a gash on one of her cheeks. Her evening gown, on the other hand, "seemed to be in good condition." Massie refused offers to be taken to a hospital, Clark said, and asked instead to be driven home--which she was.

A few minutes later, Thalia answered the phone. It was Tommie calling from a friend's home. "Something awful has happened," Thalia told her husband. "Come home."

When Tommie arrived, Thalia related a shocking story. Crying, she told Tommie that she had been gang-raped by a group of Hawaiians.

Rounding Up Suspects

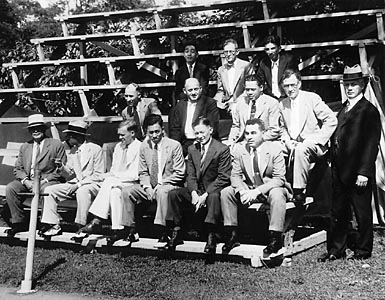

The five men arrested for the rape of Massie

About the same time that Thalia Massie jumped in front of the headlights of the car on Ala Moana Road, Agnes Peeples appeared at Honolulu's downtown police headquarters to report an assault on her at a nearby intersection. Peeples reported that after a near accident, a young Hawaiian man shoved and hit her, leaving her with a bleeding ear. The license plate of the touring car that nearly hit her, Peeples told police, was 58-985.

One hour after Peeples filed her report, police got another call. It was Tommie Massie reporting that his wife had been assaulted. Two investigators were dispatched to the Massie house. When they arrived, they listened--stunned--to Thalia's story of having been attacked by four or five Hawaiians, dragged to some bushes, and raped six or seven times. Thalia described the car as old and dark-colored. She said she could not read the license plate.

Two alleged attacks on women by Hawaiians within a very short time frame: detectives took this to be strong evidence that both attacks were carried out by the same gang. A search turned up the owner of a light tan Model A Ford bearing the license plate 58-985. The owner was an unmarried Japanese woman who lived in a poverty-stricken slum called "Hell's Half Acre." Detectives quickly determined, after visiting the owner's cottage on Cunya Lane, that the car involved in the Peeples incident had been driven that night by the woman's son, Horace Ida. They hauled Ida to headquarters for interrogation as a suspect in both the Peeples and Massie assaults.

The Peeples and Massie cases became closely linked in the minds of investigators when, after a medical examination that left an examining nurse describing Massie as "clean as a new pin," Thalia told Detective John McIntosh that she caught "a fleeting glimpse" of the license plate of the car driven by her attackers: "I think it was 58-905," she said. Only a single digit separated the license Massie reported from the one Peeples reported. This could hardly be a coincidence. It wasn't. Radio messages reporting the license number had been heard by members of the Massie party. In addition, a friend of Massie's, who went with Thalia to the hospital, had been told the license number by a detective.

With the near match on the reported license plate numbers, investigators quickly jumped to conclusions. When Ida was brought into a room with Thalia Massie, Detective McIntosh said accusingly, "Now look at your beautiful work!" Under intense grilling and believing that they faced danger only in connection with the Peeples assault, Ida finally revealed the names of four friends, all in their twenties, who accompanied him that night. In a matter of hours, Ben Ahakuelo, Henry Chang, David Takai, and Joe Kahahawai were taken in for questioning. The case was starting to look pretty solid, but just to make conviction easier, McIntosh urged another investigator to drive Ida's Model A Ford back and forth in the mud at the clearing where Massie alleged she had been gang-raped.

News of the alleged rapes and the arrests outraged Hawaii's white community. Admiral Stirling, commandant of the Naval District based in Hawaii, expressed the hope that the "brutes" would be "strung up on trees." A banner headline in Honolulu's Advertiser read "GANG ASSAULTS YOUNG WIFE" and the accompanying story told how a refined and cultured young lady "of the highest character" had been brutally raped by a gang of "fiends." A group of white businessmen posted a reward of $5,000 for evidence that would help secure convictions.

As the investigation developed, one glaring weakness in the prosecution case became obvious: it was hard to see how the suspects had the time to commit the alleged rapes. Witnesses placed the men at a dance in Waikiki until 12:05 or 12:10. They were back at the private home of a city supervisor, where a party had been in full swing earlier, by 12:30. The near accident with Agnes Peeples occurred at 12:40 at a location six miles from the scene of the alleged rapes. The Clarks picked up Thalia Massie between 12:50 and 1:00. How could the five young men drive across town after 12:40, pull Thalia into their car, then drag her out and rape her "six or seven times," while still leaving Thalia time to get up and flag down the car no later than 1:00? The timeline didn't make sense.

At the urging of Hawaii's Princess Kawananakoa (the last living symbol of Hawaii's former monarchy), William H. Heen, the only Democrat in the territory's senate, agreed to meet with--and eventually to represent--the five young men accused in the Massie rape case. After interviewing the men, Heen and his co-counsel, William Pittman, felt certain their clients were innocent.

A Jury Hangs

The Territorial Judicial Building, setting for both trials

The trial in what was generally called "the Ala Moana rape case" opened before Judge Alva Steadman in the Honolulu Courthouse (the building now houses the Hawaii Supreme Court) on November 16, 1931. Two days later, prosecutors and defense attorneys settled on a jury of seven nonwhites (including two Chinese and two Japanese) and five whites.

Thalia Massie took the witness stand first for the prosecution. In sometimes tearful testimony, Massie told jurors she left the Ala Wai Inn" about 11:35" and had walked "five or ten minutes" along John Ena Road when she was picked up by the defendants. "Two men jumped out of the car," Massie testified, and "Kahahawai came behind me and struck me on the jaw" and "was pushing me into the car." She estimated that she spent "perhaps twenty minutes" at the scene of her rape after being dragged out of the car.

In cross-examination, Thalia failed to recall making statements to the effect that her attackers were all Hawaiians or that she was unable to make identifications either of her attackers or the car's license plate because of the darkness.

Dr. John Porter, the doctor who examined Massie after her alleged rape, was at best equivocal on key questions. In response to the prosecution's question of whether it was possible "four or six men had sexual intercourse without showing [any viable sperm]," Porter answered, "It may or may not."

Prosecutor Griffith Wight called several police officers and investigators as witnesses. Officer Claude Benton testified concerning his discoveries after being sent to the scene of the alleged attack, the old Animal Quarantine Station. Benton told jurors that his examination of tire tracks led him to conclude that a car with tires consistent with those of the defendant's car had sped into the grounds at about forty miles per hour. Defense attorney Heen, however, raised serious questions about Benton's knowledge of tire treads, considerably weakening the power of his testimony. Detective Thomas Finnegan described how Massie identified three of the defendants as her attackers at her home on the day after the alleged rape. Finally, Inspector John McIntosh provided jurors with an account of the prosecution's "clinching" evidence: Massie's recall of a license plate number that varied by only a single digit from the plate riding on the back of Horace Ida's car. The prosecution rested.

Fearing a backlash if they were seen as too tough on Thalia Massie, defense attorneys adopted a strategy of presenting evidence that the police got the wrong men, rather than that no rape had ever occurred. Any suggestions that Thalia's claim was fabricated had to be made with extreme subtlety. The attorneys hoped that the jurors themselves could be counted on to note the lack in the prosecution's case of significant medical evidence supporting the rape charge.

Numerous alibi witnesses placed the defendants away from the scene of the alleged rape at critical times. Several witnesses testified that they saw the defendants at the Eagles' dance and the nearby parking lot around midnight. Others described seeing them en route to Sylvester Correa's home (where a luau had been in progress) in the minutes after the dance ended. Two Correa teenagers testified that they saw the defendants--looking to see whether there was "more beer"--in the family driveway sometime close to 12:30. With the earlier testimony in the prosecution case concerning the altercation with Agnes Peeples around 12:35 to 12:40, some jurors could be expected to begin having doubts about whether the defendants had the time for twenty minutes of gang rape in the hour between midnight and 1:00 a.m.

Those doubts likely increased when the defense produced witnesses who reported sightings of Thalia (or someone who wore Thalia's dress or looked a lot like Thalia) walking along John Ena Road shortly after midnight. A couple testified that while on foot in search of Japanese noodles, they saw a woman of Massie's height, followed by a white man, walking toward them. Both witnesses were quite sure the green ankle-length dress the woman had on was the same one Thalia wore on the night of the alleged rape. The wife told jurors that the woman they saw was "mumbling" and "stumbling."

Other witnesses raised questions about Thalia Massie's memory, which seemed to get better and better as the investigation proceeded. Detective George Harbottle, one of the first to interview Massie, testified that she first said it had been "too dark" to identify her assailants and that she had failed to get a good look at the license plate number.

Finally, defense attorneys Heen and Pittman raised questions about the integrity of the investigation itself. Most dramatically, Officer Sato testified that he and Inspector McIntosh had driven Horace Ida's car back and forth in the mud at the scene of the alleged rape--at a time before Officer Benton showed up to conduct his tire tread investigation.

Closing arguments began on December 1, 1931. For the defense, William Heen argued that the police witnesses for the prosecution had led and been "caught red-handed in framing the tire evidence to send innocent men to jail." The evidence, Heen said, proved the defendants were nowhere near the site of the rape when it occurred--if it occurred at all. He urged jurors to "be courageous" and "return a verdict of not guilty on your first ballot." Griffith Wight, for the prosecution, asked jurors to "vindicate Hawaii" and "protect your women."

The convictions that most white Hawaiians (and most people around the country following newspaper reports of the trial) assumed would follow never came. The jury deliberated for ninety-seven hours before finally giving up, unable to reach a verdict. The final vote, it was later revealed, was 6 to 6.

The Murder of Joseph Kahahawai

Police removing the body of Joseph Kahahawai for Buick sedan used in abduction

Tensions rose after the hung jury. "The Shame of Honolulu" read one banner headline, above a story that warned of the risk of rape "by gangs of lust-mad youths." Police answered numerous riot calls after fights broke out between whites and nonwhites. Defendant Horace Ida found a revolver stuck into his ribcage outside a speakeasy and was dragged into a car filled with sailors and taken to a remote cliffside location. The sailors dragged him from his car, removed his shirt, and proceeded to whip him, kick him, and slug him with a gun. A passing motorist discovered Ida and took the battered youth to the police station, where he was pronounced "lucky to be alive." Admiral Stirling called for a military takeover of Hawaii and canceled all shore leave for navy personnel.

Meanwhile, Grace Fortescue and Tommie Massie began plotting their own strategy for dealing with what they and their supporters considered to be a travesty of justice. They fretted that a second trial might produce no better outcome than the first. Police had uncovered no new evidence of guilt and there seemed no obvious way to keep nonwhites (who they suspected of having voted for acquittal in the first trial) off of a second jury. Only a confession could guarantee a guilty verdict.

An attorney friend of the Massies told Tommie that a confession made as the result of a beating would not be admissible. However, so long as a confession is extracted without force--or perhaps just so long as no bruises or marks are on the body--jurors could consider it, suggested the friend. Joe Kahahawai, according to rumors, might be the easiest defendant to crack, so Grace and Massie began to focus their scheme on him.

Under a court order, Kahahawai was required to appear daily at 8:00 a.m. at the judiciary building in downtown Honolulu to meet with his probation officer. On Thursday morning, January 7, 1932, Tommie Massie, disguised in a gray chauffeur costume and goggles, drove in a rented Buick sedan to the judiciary building. Riding with Massie was a soldier, Deacon Jones, recruited for the plot. Grace and another sailor, Edward Lord, followed behind in Fortescue's roadster. When Kahahawai left the building following his meeting, Jones strode toward him, grabbed him by the arm, and waved a crude imitation of a military summons in his face. The paper, with its misspelling, read:

TERITORIAL POLICE

MAJOR ROSS COMMANDING

SUMMONS TO APPEAR

KAHAHAWAI, JOE

Pasted below was random text from a newspaper and, in the corner of the absurd document, Grace had pasted a gold seal that was cut from a diploma Tommie had earned for completing Chemical Warfare School. Jones, with a Colt .32 to back him up, ordered Kahahawai into the car and the car sped off. As the car turned right up King Street, a friend of Kahahawai's who witnessed the abduction ran to report what had happened to officials in the judiciary building. Meanwhile, both of the conspirators' cars headed to Grace's rented home in the Manoa Valley. The cars were parked in the driveway and the human cargo unloaded and brought inside to be roped.

Radio transmissions advised Honolulu police to be on the lookout for a blue Buick sedan believed to be involved in the Kahahawai kidnapping. About 10:20 a.m., Detective George Harbottle spotted a large sedan driven by a woman with two male passengers and a drawn back shade. The drawn shade aroused suspicion, so Harbottle decided to investigate. The detective followed the car as it headed out along a coastline road in the direction of a steep cliff overlooking the Halona Blowhole. The car picked up speed. Soon another police car joined the chase. The driver of the Buick ignored Harbottle's orders to pull over. Harbottle fired shots at the vehicle as it sped past. Finally, the detective managed to overtake the fleeing car and force it off the road.

With gun drawn, Harbottle approached the car. In the rear seat, the detective saw a blood-soaked bedsheet wrapped around body. He placed under arrest the occupants of the car, Grace Fortescue, Tommie Massie, and Edward Lord.

Investigators arriving at the Fortescue house were greeted by Deacon Jones, holding a glass of whiskey in a room he had recently cleaned of blood. Officers brought Jones to the police station for questioning. They also gathered evidence, including rope, guns, "masquerade outfits," buttons that had been ripped from underclothing, and a blood-soaked towel.

Admiral Stirling, aghast to think of Grace or his soldiers spending even a single night in jail, secured judicial approval to house the four prisoners at a decommissioned ship in Pearl Harbor. Messages of sympathy and support poured in, as the four conspirators enjoyed the luxury accommodations provided by the United States Navy. Some newspaper reports around the country referred to the murder as "an honor killing."

In an increasingly divided Hawaii, more mourners showed up for the funeral of Joe Kahahawai than for any other in the island's history--save for the funeral, fifteen years earlier, of its last queen. Among the two thousand persons attending the ceremonies, one remark was heard most frequently: Joe's death proved that whites "are shameless." The islands had witnessed a lynching, not an honor killing.

Clarence Darrow's Last Trial

On January 21, a grand jury convened to consider whether to indict Grace Fortescue, Thomas Massie, Deacon Jones, and Edward Lord for the kidnapping and murder of Joe Kahahawai. For two days, the twenty-one grand jurors listened as County Attorney Griffith Wight presented witnesses.

The majority of the jurors seemed inclined not to indict--and probably would not have done so but for the determined efforts of Judge Albert Cristy. Judge Cristy reminded the grand jurors that their job differed from that of a trial jury. They were not to make conclusions about guilt or innocence, but rather to determine whether there was enough credible evidence of guilt to justify putting the defendants on trial. When the jury foreman reported back to the judge later that the jury stood 12 to 9 against indictment, Cristy hauled the grand jurors back to his courtroom for another lecture on the function of a grand jury. Jurors were told to ignore their own "inner feelings" and return an indictment if the evidence showed a crime was committed and that these defendants were responsible. Jurors who could not do their duty, the judge suggested, "should resign immediately." Three days later, as deliberations resumed, the judge asked the grand jurors "to lay aside all race prejudice" and consider how civilization depends for its very existence on the rule of law. Eventually the jurors came around to seeing it Cristy's way. By a vote of 12 to 8, the grand jury finally voted to indict all four defendants for second degree murder.

At the time the grand jury returned its indictments, America's most famous defense attorney, Clarence Darrow, was seventy-five and some seven years into his retirement. The Depression, however, had taken a toll on the investments that he and his wife Ruby assumed would guarantee them golden years of European travel and fine living. With his record of defending society's underdogs and his unusually progressive views on racial issues, Darrow seemed an unlikely choice to represent four whites accused of lynching a Japanese American. A large fee and the promise of a sensational trial in a tropical paradise proved enough to lure the great man back into the courtroom battlefield. In his memoirs, Darrow attributed his decision to take the case (for the then-princely sum of $30,000 plus expenses) to his need for money, his longing to see Hawaii, and his interest in cases that raised profound issues of psychology.

On March 24, Clarence and Ruby Darrow, together with Darrow's assistant defense attorney George Leisure, stepped off the ship Malolo and met a large party of reporters and greeters that had gathered at the Honolulu dock. As photographers scrambled for pictures of Darrow wearing a lei that someone had draped around his neck, Darrow complained: "Can't I take off these jingle bells? I look like a decorated hat rack." He left the pier and headed directly to Pearl Harbor to meet with his clients.

Clarence Darrow, Thalia Massie, and Grace Fortescue walking

It was beyond dispute that the four defendants had caused the death of Joe Kahahawai, so Darrow was left to consider what extenuating circumstances would be most likely to turn a jury toward acquittal. Temporary insanity seemed a promising idea. Darrow arranged for a team of prominent psychiatrists to travel from the mainland to meet with his clients.

The prosecutor assigned to the case, John C. Kelley, understood that under a felony murder theory he did not have to prove which of the four defendants fired the bullet that killed Kahahawai. He suspected Jones, but it didn't matter. If any one of the four was the killer, then all four involved in the kidnap plot were equally guilty. Kelley knew Darrow to be a flamboyant, instinctual courtroom lawyer who often had little patience for statutes and case law. He suspected that Darrow would try to convince jurors that the "unwritten law" justified the actions of his clients.

Jury selection began on April 4 in the packed courtroom of Judge Charles Davis. (The trial was transferred from Judge Cristy to Judge Davis on the order of Cristy following the defense's submission of an "Affidavit of Prejudice" against Cristy for his handling of the grand jury proceedings.) A week of battling over prospective jurors--prolonged by the fact that many on the panel wanted no part of the controversial trial--produced a racially mixed final jury comprised of seven whites and five nonwhites.

In his opening statement for the prosecution, John Kelley told jurors that the evidence would prove that Kahahawai was shot, then dragged to a bathroom where he bled to death. Kelley then called his first witness, Edward Ulii, who described the abduction. He identified Deacon Jones and Grace Fortescue as among those who he saw kidnap his cousin after they walked out of the judiciary building. Skipping for now the murder, Kelley next presented witnesses who described the capture of the defendants. Detective Harbottle identified the three people he found in the Buick. Other police officers identified incriminating evidence found in the car, including a bloodstained shirt with a bullet hole in its left side. Kelley held up the shirt and then gave it to the jury foreman. As each juror in turn examined the shirt, Joe Kahahawai's mother, seated near the jurors, wept openly.

Moving on to the murder itself, Kelley presented the coroner with a full-color set of anatomical drawings that made clear that Kahahawai had been sitting down, and his killer standing, at the time of his shooting. Photos of Grace's bloodstained floors were introduced into evidence. Detectives reported finding rope matching that found on Kahahawai's corpse--and then Kelley passed to the jurors the actual rope found on the body. Bloody sheets were held up for jurors to see. Detective Arthur Stagbar told jurors how he found buttons that matched the buttons on Kahahawai's shirt underneath Fortescue's washbasin. A gun salesmen testified that the bullet removed from Kahahawai's body matched an empty cartridge found in the pocket of Deacon Jones, and that the bullet could have been fired from the .32 caliber Colt he had sold to Jones. The evidence of guilt seemed overwhelming. Kelly rested his case after calling Joe Kahahawai's mother to the stand to identify her son's clothing.

Prosecutor John Kelley examines murder evidence

"The defense calls Lieutenant Thomas H. Massie." Massie took the stand as Darrow's first witness. Darrow asked Massie about the night of September 12: "Do you remember an incident of going to a dance or party?" As Massie launched into a narrative about the events leading to the alleged rape of his wife, Kelley objected, arguing that the Ala Moana case was relevant only if it caused the insanity of one of the defendants. That is exactly what I hope to prove, Darrow announced, adding that if the one who shot the pistol was insane, all the defendants should be equally innocent. Judge Davis allowed Darrow to proceed with his line of questioning.

Massie described the agony caused by his failure to protect his wife from a rape in which Kahahawai was supposedly the most brutal of a brutal gang of rapists. He testified that as he held Thalia after her ordeal she cried, "I want to die! I hope to die!" In the nights that followed, Massie said, his wife would rouse from her sleep shouting, "Don't let him get me!" His wife's distress led to his own set of problems: weight loss, sleep loss, and fear that his wife might become diseased or pregnant as a result of the attack. His last fear was realized, Tommie told jurors. The couple decided to abort her pregnancy: "I took her to the hospital and Dr. Withington performed the operation." Women in the courtroom dabbed their eyes with handkerchiefs as Massie ended his testimony for the day.

After court was canceled the next day because Darrow was too hung over to attend (he claimed an attack of gastritis), Tommie resumed his testimony. Darrow's questions took his witness to the murder scene. Tommie described seating Kahahawai in Grace's living room and then picking up the .32 automatic owned by Deacon Jones. The witness told jurors that Kahahawai continued to maintain his innocence in the face of his barrage of questions--until he finally broke:

I said, "Now go a head and tell the whole story. You know your gang was there." And suddenly he said, "Yes, we done it." The last thing I remember was that picture that came into my mind, of my wife when he assaulted her and she prayed for mercy and he answered with a blow that broke her jaw.

Q: Did you have a gun in your hand when you were talking to him?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Do you remember what you did?

A: No, sir.

Q: Do you remember what became of the gun?

A: No, I do not, Mr. Darrow.

Q: Do you know what became of you?

A: No, sir.

Darrow's two psychiatric experts testified Tommie was temporarily insane at the time of the shooting. One expert explained that the strain of his wife's misfortune and the trigger of Kahahawai's confession caused Tommie to suffer an impaired state of consciousness and lapse into a reflexive, automatic pattern of action. The other expert suggested the strain of recent events had caused Tommie's ductless glands to alter his body chemistry. "Chemical insanity," was the doctor's diagnosis.

Darrow called Thalia Massie to the stand. Thalia offered a new, more detailed version of the alleged rape in which Kahahawai refused her request to pray and then "hit me as hard as he could on the jaw." When she pleaded, "Please do not hit me anymore," Kahahawai--according to her story--replied, "Well, shut up then" and swore at her. Thalia testified that she learned about Kahahawai's murder from Deacon Jones. After telling her the news, according to Thalia, "He asked me for a drink and I poured him one but he said, 'That's not enough,' so I filled his glass." Many spectators cried during Thalia's emotional testimony. Darrow, however, was worried. He noticed that two jurors were dry-eyed and cleaning their nails.

The highest drama of the trial played out during John Kelley's cross-examination of Thalia Massie. When Kelley handed Thalia a psychiatric questionnaire she had filled out some years earlier (one that suggested serious marital problems), the witness snapped: "Where did you get this? Don't you know this is a confidential communication between a doctor and patient? I refuse to say whether that is my handwriting or not." Thalia proceeded to tear the questionnaire in two and then rip it into smaller pieces, finally tossing the shreds into the air. Spectators erupted in applause. "Thank you, Mrs. Massie. At last you've shown your true colors," Kelley remarked. Thalia almost stumbled from the witness stand into the arms of her husband who had moved forward to catch her. With her arms firmly around her husband, Thalia shouted hysterically, "What right has he got to say that I don't love you? Everybody knows I love you." Even Clarence Darrow seemed stunned by what he just witnessed: "I've seen some pretty good court scenes, but nothing like that one." The defense rested.

After rebuttal testimony from a pair of psychiatrists testifying for the prosecution (unsurprisingly, they declared Thomas Massie perfectly sane at the time of the murder), summations began. Clarence Darrow's last argument was carried live on radio stations across the country. Every seat in the hushed courtroom was filled as Darrow recounted how the unbearable suffering of the Massies had driven Grace Fortescue to extreme action in defense of her loved one. For over four hours, Darrow's voice rose and sank, his hands waved through the sultry courtroom air, he bent and straightened--and occasionally wiped away tears. He emphasized the injustice of closing "the black gates of a prison" on his clients "on top of all they have suffered." After a lunch recess, Darrow moved toward his conclusion:

If you want to send [Grace] to the penitentiary, all right, go to it. If this wife and mother, this husband and these faithful boys go the penitentiary, it won't be the first time the penitentiary has been sanctified by its inmates. It won't be the first time the name of the jail will be remembered when every jailer has been forgotten. When people come here, the first thing they will wish to see is where the mother and husband are confined. If it should happen, that building will be the most conspicuous building on this island and people will wonder at the cruelty and injustice of man.

After a lunch recess, Darrow moved toward his conclusion. He praised Hawaii--"this fairy land...with its green mountains and its ocean waves that turn to every hue of the rainbow"--and its "kindly dispositioned people." He ended with a plea for mercy: "I ask you to be kind, understanding, considerate--both to the living and the dead."

Massie trial jury

John Kelley urged jurors to put aside Darrow's emotionalism and return convictions. "The best you can say for Massie," Kelley argued, "is that he had a very convenient memory. The defense must take you for a bunch of morons. Is there one law for strangers in our midst and one for you and me? We must abide by the law or descend into chaos." Kelley warned of dire consequences if the jury failed to convict: "If the serpent of lynch law is allowed to raise its head in these islands, watch out. Watch out!"

On April 27, after listening to Judge Davis's detailed instruction, the jury settled into its deliberations. Forty-seven hours worth of debates later, the jury had still not reached a verdict and Judge Davis called them back into the courtroom. "Is there any possibility of arriving at a verdict in the near future?" the judge asked the jury foreman. To the surprise of most observers, the foreman said that he thought a verdict might be reached. The jury returned to its room. Thirty minutes later, the announcement came: a verdict had been reached in the Massie case. After reporters and attorneys and defendants reassembled, the verdict sheets were read by the Clerk of Court. For each defendant, the same words came: "Guilty of manslaughter. Leniency recommended."

Epilogue

The jury asked for leniency for the four defendants and that is what they got. While Darrow vowed to take an appeal to the U. S. Supreme Court if necessary, and while members of Congress advocated for a law authorizing a presidential pardon and even urged the impeachment of Judge Cristy, Governor Lawrence Judd (who did have pardon authority) pondered what to do. Navy brass and powerful business figures in the states were demanding full pardons for all. Judd, however, felt pressure not to be seen as condoning lynching, a perception which would outrage important ethnic groups in his state. Then, according to defense attorneys who at the time were with Judd in his office discussing options, the governor's phone rang. On the other end of the line was President Herbert Hoover, who urged Judd to avoid jail time for the four.

Without explanation, sentencing in the case was moved up two days, to the following morning, May 4. As the bailiff ordered each defendant to stand in turn, Judge Davis imposed sentence on each: ten years imprisonment at hard labor. Court adjourned and the sheriff took custody of the four prisoners and led them on a walk to the Governor's suite. A few minutes later, Judd read a short statement to reporters who had been summoned to the mansion: "I hereby announce I have commuted their sentence to one hour, to be served in the custody of the High Sheriff." Grace Fortescue turned to the governor and said, "This is the happiest day of my life." Deacon Jones, who three decades later would admit to firing the bullet that killed Joe Kahahawai, left to send a telegram to his mother in Massachusetts: "Dear Mom: Will be home soon. Keep the coffee hot. Albert."

Princess Kawananakoa spoke for many less powerful, and less white, voices in Hawaii. "Are we to infer from the Governor's act," the princess wondered, "that there are two sets of laws in Hawaii--one for the favored few and one for the people generally?"

The governor seemed to have second thoughts about his commutation. He refused all demands for a full pardon and wrote a letter to the Secretary of Interior blasting Navy officials for their racist attitudes and requesting a reassignment--which was granted--of Admiral Stirling.

In October, the Pinkerton Detective Agency handed Governor Judd a 279-page report of the Massie case. The report concluded, "It is impossible to escape the conclusion that the kidnapping and assault was not caused by those accused." Later, John Kelley announced that all rape charges were being dropped against the Ala Moana defendants.

David E. Stannard, in his book Honor Killing: How the Infamous "Massie Affair" Transformed Hawai'i, argues that the case changed Hawaiian society as surely as it changed individual lives. The trials emboldened prominent members of Honolulu's white society to speak out against the powerful business oligarchy that for so long had determined the social order of the islands. The case also convinced Hawaiian, Japanese, and Chinese community leaders that their common interests were more important than the differences that had previously divided them. Various ethnic groups began to think of themselves as Pacific Islanders or Asians or natives and identified less with their individual countries of origin. Politics in Hawaii shifted, with nonwhites voting in record numbers. What had been a Republican territorial legislature became a Democratic one. Over time, Hawaii lost some of its political uniqueness, but it still is a state with a strong record of progressive reforms. David Stannard attributes those achievements to "an earlier time, when a semblance still remained of the idealism and solidarity that emerged following confrontations with raw, white power during the tumultuous rape and murder trials of 1931-32."