In 1925, the Indiana KKK was the largest state branch in the Klan's "Invisible Empire." One out of every three white males in Indiana claimed membership in the organization. It was hardly an exaggeration to say the Klan owned the state, dictating decisions from the governor’s office to county sheriffs’ offices.

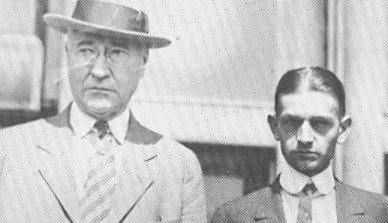

But the conviction in November of D. C. Stephenson, the powerful grand dragon of the Indiana Klan, for the murder of Madge Oberholtzer led to a dramatic decline in the organization's membership and political influence. What began as a vicious sexual assault on a night train from Indianapolis to Chicago ended with arrests of Indiana's governor and other high state officials.

Background

On a hot July 4, 1923 in Kokomo Indiana's Melfalfa Park, the new grand dragon addressed the largest Klan rally ever held in the United States. Estimates of the crowd ranged upwards of 100,000 people. Five years later, in a somewhat fictionalized retelling of the story, the Atlantic Monthly reported that D. C. Stephenson climbed out of a private airplane and told the assembled tens of thousands: "My worthy subjects, citizens of the Invisible Empire, Klansmen all, greetings! It grieves me to be late. The President of the United States kept me unduly long counseling upon vital matters of state." The fact that the Atlantic Monthly's questionable version of events has so often been repeated is testament, as Stephenson biographer William Lutholtz observed, to "bravado and bluff, the incredible audacity, that formed the heart of Stephenson's life." In fact, Stephenson's speech that day was entitled "Back to the Constitution." He denounced political corruption, American imperialism abroad, and called for an end to deficit spending. He ended his hour-long, enthusiastically received talk with the cry, "Where there is no vision, the people perish!" All in all, there was scarcely a phrase in the speech that would embarrass a major party candidate today. There were better places than a huge rally attended by media from several states to deliver the KKK's anti-Catholic, anti-black, anti-Jewish message.

That night, Stephenson, in his newly-won golden orange robe and hood, enjoyed the conclusion of the "Konklave in Kokoma." A Klan parade, with robed high Klan officials on horseback and a dozen floats wound its way through town. "Onward Christian Soldiers" blared from a forty-piece marching band. When the parade was over, the crowd moved to Foster Park and sung hymns such as "The Old Rugged Cross" around a sixty-foot-high fiery cross. Fireworks streaked through the nighttime sky. Stephenson soaked it all in. He was, he thought, soon destined to be the most powerful man in Indiana.

Stephenson did become a man to be reckoned with in Indiana politics. (In fact, his reach extended beyond the Hoosier state, as Stephenson served as king kleagle of seven other Midwestern states as well.) Within a few weeks of his installation as grand dragon, Stephenson was entertaining politicians on his new yacht. Among those who sailed Lake Erie on his yacht were a U. S. senator, congressmen, judges, governors, and several state legislators. In the 1924 elections, Stephenson helped build the Klan into a potent political force. Candidates favored by the KKK--white Protestants all--benefited from the door-to-door campaigning of Klan members, who distributed printed slates of Klan-endorsed candidates with a wooden clothespin attached to each. The perfect candidate, in Stephenson's view, was a nervous one who thought he needed the voters that the KKK could bring out, and was willing to promise support for the Klan's agenda in return for that vote. One such candidate, it turned out, was Ed Jackson, the man who would become governor of Indiana.

While his political influence grew, Stephenson's relationship with the KKK's Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans (national head of the organization) soured. The growing feud between the two men over finances and priorities led Stephenson to resign as grand dragon in the fall of 1923, but by May 1924 he reclaimed the title of grand dragon of a new Indiana Klan, largely independent of the national organization. Stephenson's feelings for Evans are aptly demonstrated by his description of the Klan's leader in a letter to a friend: "The present national head is an ignorant, uneducated, uncouth individual who picks his nose at the table and eats peas with his knife. He has neither courage or culture." In a speech to Indiana Klan members, Stephenson predicted great things for his state organization: "We are going to Klux Indiana as she has never been Kluxed before!...And the fiery cross is going to burn at every crossroads in Indiana, as long as there is a white man left in the state!"

Rumors concerning a dark side of D. C. Stephenson began to emerge. Time and time again, reports surfaced of attempted rapes, sexual assaults, or inappropriate sexual encounters--almost all after he had been drinking. Shortly after the Kokomo klonvocation, a woman told police that Stephenson attempted to have sex with her in his car and that he "is a beast when he is drunk." In Ohio, he plead guilty to indecent exposure after a deputy sheriff caught him with his pants down next to a young woman in a parked Cadillac on the side of a highway. In January 1924, Stephenson tried to have forced sex with a manicurist sent to his hotel room, and punched out a bell-boy who attempted to come to the woman's rescue. In the fall of 1924, a young actress attending a party at Stephenson's home told investigators that he had locked her in a room, knocked her down, bit her, and "tried to force himself on me." By early summer of 1924, Hiram Evans saw Stephenson's pattern of intoxication, biting, and attempted rape as a means to rid the Klan of his nemesis for good. He proposed trying Stephenson before a Klan tribunal on several charges, including habitual drunkenness and demonstrating disrespect for virtuous womanhood. In late June, the tribunal found him guilty on six charges, called for his "banishment forever," and published a fifty-page report on his misdeeds. Stephenson responded by calling the banishment and the allegations against him the shameful plot of the southern Klan.

Stephenson, taking a lower profile in Indiana Klan activities, turned his attention in the fall of 1924 to getting Ed Jackson elected governor of Indiana. In November, Jackson, a Republican, won the governorship by more than 125,000 votes. With Indiana's U. S. Senator in failing health, Stephenson told friends that he expected Governor Jackson might appoint him to be the Hoosier state's new United States senator. The future for D.C. Stephenson looked very bright.

For Ed Jackson's inauguration on January 12, 1925, event planner Stanley Hill recruited a woman he was dating, a twenty-eight-year-old manager of a reading circle named Madge Oberholtzer , to help with name tags for the banquet hall. Hill placed himself at the same table as Stephenson and during the dinner Hill introduced Madge to the Klan leader. Later, when the orchestra began to play, Stephenson asked Oberholtzer to dance. Over the next couple of months, D.C. and Madge would see each other at another party and dine together on at least a couple of occasions. Stephenson also hired Madge to help write a book that he hoped the new legislature would make required reading in Indiana public schools, a book on nutrition called One Hundred Years of Health.

Stephenson succeeded in pushing through House Bill 287 on March 9, 1925. The bill ordered that public schools teach a course in diet and nutrition. Only one text could meet the specific requirements established in H.B. 287: Stephenson's own One Hundred Years of Health. Sales of the book, which would be Madge Oberholtzer’s job to write, could net Stephenson a small fortune.

When not pushing his legislative schemes, Stephenson entertained. He hosted parties that ranged from respectable black-tie events to Roman orgies. At one such party, Stephenson, dressed as a satyr, lashed naked women with a whip as they pranced around the room.

The Crime

On March 15, 1925, Madge returned to her home around 10 P.M. after a taking a spin in the country with an old friend. When she arrived, her mother told her that D.C. Stephenson's secretary had called with an important message while she was out, and that she should return the call. Stephenson answered her call. He told Madge that he was leaving for Chicago and had to see her about something "very important" before he left. Stephenson told her to expect one of his bodyguards to stop by her house shortly to escort her to his house. Madge, wearing a black velvet dress and a coat, walked out the door into the late winter night with a man she had never seen. His name, she would learn later, was Earl Gentry.

When she arrived at Stephenson’s mansion, she found he had been drinking. When Madge declined an invitation to drink, Stephenson and the other men insisted. She drank three glasses of liquor and vomited. Stephenson proposed that she join him and the other men on a trip to Chicago. Later, in a dying declaration recorded by her lawyer, Madge described what happened next:

Stephenson said to me, "I want you to go with me to Chicago." I remember saying I could not and would not. I was very much terrified and did not know what to do. I said to him that I wanted to go home. He said, "No, you cannot go home. Oh, yes! You are going with me to Chicago. I love you more than any woman I have ever known." I tried to call my home on the phone but could get no answer... They all took me to the automobile at the rear of Stephenson's yard and we started the trip....I begged of them to drive past my home so I could get my hat, and once inside my home I thought I would be safe from them. They drove me to Union Station in the machine, where they had to get a ticket....”

After boarding the train at Union Station, Stephenson and Gentry led her at once into a drawing room. Soon after the train pulled out of Indianapolis, Stephenson grabbed the bottom of Madge's dress and pulled it over her head and she tried unsuccessfully to fight him away. Soon Stephenson stripped her naked and shoved her into the lower berth. He attacked her viciously. He tried to penetrate her. He chewed her all over her body; bit her neck and face; chewed her tongue; chewed her breasts until they bled and chewed her back, her legs, and her ankles. Madge passed out.

In the early morning, at 6:30 a.m., the train pulled into the station at Hammond, Indiana. Gentry shook Madge awake and told her they were leaving the train. Stephenson was flourishing his revolver. Madge repeatedly begged the Klan leader to shoot her, but he put the gun away in his grip. The two men led Madge to the Indiana Hotel, where Stephenson registered for himself and wife under the name of Mr. and Mrs. W. B. Morgan. Once in room 416, Madge pleaded with Stephenson to send a telegram to her mother. Stephenson complied, but dictated the contents.

While Stephenson ate a hearty breakfast served in their room, Madge ate nothing. Gentry tried to clean up Madge’s wounds, which continued to ooze blood. Watching the clean up, Stephenson admitted, “I’m three degrees less than a brute.” “Your worse than that,” Madge replied.

By this time, Madge had recovered sufficiently to ask to be driven to a drug store so that she might purchase some rouge. While Stephenson's bodyguard "Shorty" waited outside in a car, Oberholtzer purchased a box of bichloride of mercury tablets, a highly toxic poison, and put them in her coat pocket. Once back at the hotel, Madge waited until Stephenson was asleep. She described what she did next: "I laid out eighteen of the bichloride of mercury tablets and at once took six of them; I only took six because they burnt me so." She laid down on the bed and soon became very ill, vomiting blood. Discovered reeling in pain, Madge admitted taking poison. An alarmed Stephenson first proposed taking her to the hospital to have her stomach pumped, but Madge refused, and the threat of her spilling the beans about the rape caused him to reconsider. Eventually, the men decided to load Madge into the back seat of an automobile and head back to Indianapolis.

Madge made the journey back in agony, screaming for a doctor or pain relief most of the way. She begged Stephenson to leave her along the road, in the hope that someone would stop and take care of her, but the car just sped on. Stephenson and Gentry spent the road trip drinking, while "Shorty" drove. Madge, meanwhile, had come to regret taking the poison and now wanted to live.

Stephenson, according to Oberholtzer's account, did not seem overly concerned with his plight, though he remarked, "This takes guts to do this, Gentry. She is dying." Stephenson predicted he would escape punishment and that "my word is the law." Upon reaching Indianapolis, they drove straight to Stephenson's house only to find Madge's mother waiting by the front door. After "Shorty" lied about Madge's whereabouts and Mrs. Oberholtzer left, the three men carried Madge to a room above Stephenson's garage.

Madge's condition seemingly improved over night. About noon on Tuesday, March 17 (two days after the rape), a Stephenson bodyguard named Earl Klinck carried her back to her home, but only after she was warned several times to say that her injuries and suffering were the result of "an automobile accident." Stephenson, she said, told her, "You must forget this, what is done has been done. I am the law and the power." Klinck, after telling Eunice Shultz, a roomer in the Oberholtzer house, that Madge had been hurt in a car accident, carried Madge into the house and upstairs and placed her on her bed. Leaving quickly, he told Shultz, "My name is Johnson from Kokomo and I must hurry."

Madge on Her Deathbed

Eunice Shultz found Madge pale and groaning on her bed. She bore bruises on her cheek, chest, and breast, stomach, legs, and ankles. The skin on her left breast was open. Madge opened her mouth and spoke: "Oh!, dear mother. Mrs. Shultz, I am dying." Doctor Kingsbury, summoned to the house by Schultz, determined Madge to be in a state of shock. Her body was cold and her pulse rapid. When asked her how she was injured, Madge first replied, "When I get better, I will tell you the whole story." Then, some minutes later, she told the story of the rape by Stephenson on a train and her ingesting of poison the next day. Kingsbury collected a urine sample which, after testing, showed evidence of acute kidney inflammation. Every day, for the next four weeks until her death, Dr. Kingsbury would visit and treat his patient.

On March 28, Dr. Kingsbury concluded Oberholtzer had no chance for recovery. When he told his patient the bad news, Madge took it well: "That is all right doctor, I am ready to die. I understand you doctor. I believe you and I am ready to die." What Kingsbury could not tell Madge is exactly why she was dying, only that it seemed to be a combination of all that had happened to her, the shock, possible infection from the bites, loss of rest, and the action of the poison on her system and her lack of early treatment.

When Asa Smith, an attorney and a friend of the Oberholtzer family, learned that Madge's prospects were grim, he decided to take a statement for use in a possible criminal trial involving Stephenson and other defendants. A statement made in the belief of one's own imminent death is called "a dying declaration" and is generally admissible in court, even though obviously not subject to cross-examination. Oberholtzer told the attorney and from the statements so made by her to him, he prepared and had transcribed a dying statement, which was read to her and in which she made corrections. Madge signed the 3000-word statement, saying therein that she had no hope of recovery. Two weeks later, on the morning of April 14, 1925, with her parents and a nurse by her side, Madge died.

Getting Ready for Trial

In the first days after the assault, when hope still existed for a full recovery by Madge, Asa Smith told Stephenson that he would sue for what he had done. Smith discussed with Stephenson a monetary settlement that would provide some compensation for the Oberholtzers but spare the family the embarrassment of a criminal or civil trial. Smith and attorneys for Stephenson discussed a settlement. Stephenson offered the family $5,000, an amount Smith found insultingly low. Negotiations broke off when word came of Madge's deteriorating condition.

Marion County prosecutor Will Remy, one of the few officials in the county not under Stephenson’s heavy thumb, prepared a warrant for Stephenson's arrest on kidnapping and assault charges on April 2. At his arraignment four days later, Stephenson was asked by a reporter for a comment on the case. "I refuse to discuss such trivial matters, " Stephenson replied. "How would you like to be fishing right now and watch a red darter spinning in front of a bass?" Pressed further, Stephenson harrumphed, "Nothing to it! I'll never be indicted!"

But in early April, Stephenson was indicted by a grand jury. Remy ordered Stephenson’s arrest. Arriving at Stephenson’s home, a detective served the warrant just minutes before Stephenson, suitcase at his side, was intending to flee Indianapolis.

Attitudes in Indiana towards Stephenson were changing rapidly. Reports concerning the rape on the train appeared in newspapers throughout the state. Public indignation with Stephenson grew by the day, reaching a fever pitch by the time of Madge's funeral. On that day, Judge James Collins announced that he was rejecting a defense motion to quash the indictment. Stephenson would face trial--and now it would be a murder trial.

In late April, the coroner's office released a report on the autopsy of Madge Oberholtzer. Based on a chemical analysis of Madge's internal organs, the report concluded that her "death was due to mercurial poisoning, self-administered." The report complicated the prosecution's efforts as it could now be anticipated that the defense would contend that Stephenson's rape was not the proximate cause of her death and that therefore he could not be convicted of murder. If infections resulting from the rape were not the cause of death, prosecutor Remy might now have to prove that duress from the rape and kidnapping was so closely connected to Madge's decision to ingest the mercury tablets as to make it a foreseeable consequence of the rape--and that would be a difficult task.

Eight days after Stephenson pleaded "not guilty," defense attorney Eph Inman filed a motion for a change of venue, which was granted. The Stephenson trial was headed for Noblesville, Indiana and the courtroom of Judge Fred Hines. Also facing charges for the murder of Oberholtzer were Stephenson's companions on the notorious train trip, Earl Klinck and Earl Gentry.

The defense's first attack was aimed at Madge's dying declaration. In a hearing before Judge Hines, the defense sought to prove that Oberholtzer died of mercurial poisoning, not infection resulting from Stephenson's bites, and that she was not in a sound state of mind at the time she gave her dying declaration. Inman called doctors to the stand, each of which stated his opinion that the mercury tablets were the cause of death. Then he called attorney Asa Smith, who admitted that he--not Madge--wrote the dying declaration, although he insisted every word of it was read to Madge and she made several changes in the document. Inman failed to produce any evidence that Madge was not in full possession of her faculties at the time the declaration was prepared. Accepting defeat as inevitable, the defense withdrew its motion to exclude the declaration from the trial.

Meanwhile, news accounts of Oberholtzer's rape and death caused public opinion to swing rapidly against the Klan. Sentiment against Stephenson swung even more dramatically, thanks in part to the efforts of Imperial Wizard Evans, who saw the trial as a way of ridding himself of his trouble-making Klan rival. Women began calling the prosecutor’s office with stories of their own sexual assaults at the hands of Stephenson—stories they were afraid to share until the indictment. Five hundred women rallied by the Marion County Courthouse, demanding that Stephenson not be released on bail. He wasn’t.

The Trial

The Prosecution Case

The trial of D.C. Stephenson, Earl Klinck, and Earl Gentry for the kidnapping and murder of Madge Oberholtzer opened on October 12 before Judge Will Sparks. (Sparks replaced Judge Hines, after Hines accepted the defense's motion for a new judge.) Sparks had a reputation for being an even-handed judge. Only after a record 260 potential jurors were interviewed, and the judge's patience with the process finally exhausted, was a jury of twelve men, ten of whom were farmers, finally seated.

Opening arguments were presented on October 29 in the three-story brick courthouse. Charles Cox, for the prosecution, told jurors that the state's star witness, from the grave, would be Madge Oberholtzer:

“Clean of soul, but with her bruised, mangled, poisoned and ravished body, standing by her grave's edge, with the shadowy wings of the dark angel of death over her, will tell you...the story of her entrapment, of her being drugged, kidnapped, assaulted, beaten, lacerated with beastly fangs, and finally, as the culmination of indignities and brutalities unheard of in a civilized community before, how she was forced by the loss of all that a good woman holds dear, to take the deadly poison that contributed to her untimely death.”

A series of prosecution witnesses described events and Madge's condition in the days after Stephenson's assault. The state's first witness, Matilda Oberholtzer, Madge's mother, described her daughter’s sudden departure on the night of Sunday March 15, and not seeing her again until two worrisome days later. She testified that when she saw her daughter the following Tuesday "her breasts had open wounds all over."

The boarder at the Oberholtzer's, Eunice Shultz, testified next and identified defendant Earl Klinck as the man who claimed to be "Mr. Johnson from Kokomo" and said that Madge had been "hurt in an automobile accident." She told the jury that Made said to her, “I’m dying, Mrs. Shultz.”

Dr. John Kingsbury, the doctor who examined and treated Madge, testified that she told him "she expected and wanted to die." Kingsbury told jurors that a week or so later he came to the conclusion that Madge's condition was deteriorating and was hopeless. Kingsbury testified that the lack of prompt treatment in the first several hours after Madge took the poison most likely ended her chances of recovery. Dr. Kingsbury also testified that infections resulting from wounds to her breast and cheek “most certainly hastened her death.” George Oberholtzer, Madge's father, testified next and reported that Madge "begged and begged" her abductors to get her to a doctor, but they refused.

Attorney Asa Smith, the family friend who prepared the dying declaration signed by Madge, presented the testimony that cleared the way for the introduction of Madge's account into evidence. Smith admitted that he wrote the declaration in his office, but testified that it was based on notes from his bedside conversation with the dying woman. The attorney said that he went over each line of the statement with Madge, making any corrections that she suggested. On cross-examination, defense attorney Eph Inman raised questions about the declaration, probing Smith about why he didn't know the name of the notary public who acknowledged Madge's signature and suggesting that the statement was really based more on Smith's imprecise memory than Madge's actual words. When Will Remy tried to enter the dying declaration into evidence, the defense objected on the ground that Madge's death resulted from her suicide, not the actions of any of the defendants. Judge Sparks, however, in the most important single decision in the trial, admitted the declaration and allowed Remy, in a deliberate cadence, to read it to the jurors. Courtroom spectators sat rapt as Remy read, the only noise came from the sobbing of Madge’s mother.

The next phase of the state's case consisted of a series of witnesses who placed Madge on the train with the other defendants, and then at the Hammond Hotel. A black porter on the train testified that he heard Madge say to Stephenson, "Oh dear, put the gun up. I am afraid of it." A night clerk at the hotel testified that he had checked Stephenson and Oberholtzer into room 416 under the name "Mr. and Mrs. W. B. Morgan." A bellboy reported seeing bruises on Madge's cheeks.

Finally, the prosecution presented evidence that the actions of Stephenson and the other defendants led directly to Madge's death. Beatrice Spratley, Madge's nurse, told jurors that a laceration on Madge's left breast became infected and the infection was still visible at the time of her death. Dr. Virgil Moon, who performed the autopsy on Oberholtzer, testified that "the immediate cause of death was an infection carried through the blood stream, localizing in the lung and in the kidney." He expressed his opinion that but for the lacerations received during her assault, Madge would have recovered from her poisoning. Newspaper accounts trumpeted the medical testimony as a severe blow to the defense case.

The Defense Case

In its case, the defense strongly contested the prosecution suggestion that Madge's death resulted from the mercury tablets she voluntarily ingested. Dr. Orville Smiley and Dr. J. D. Moschelle, both Indianapolis doctors who had treated cases of mercury poisoning, testified that in their opinions the cause of death was "bichloride of mercury," not an infection. Coroner Dr. Paul Robinson, disagreeing with the doctor who performed the autopsy, told jurors that the official verdict of his office on the cause of Madge's death was also mercury poisoning.

After presenting yet another doctor to testify that mercury--not lacerations--killed Madge, the defense called to the stand a witness, Cora Householder, who the defense planned to use to undermine the prosecution's suggestion that Oberholtzer was as pure as the driven snow. Householder would, if permitted, testify that Madge had been having an affair with her estranged husband. Judge Sparks cut the defense questioning off, sustaining a prosecution objection to Householder's testimony as irrelevant and inadmissible.

The defense next presented dentist and KKK organizer Vallery Ailstock, who told jurors he once had Madge ask him for a glass of gin in the company of Stephenson in Columbus, Indiana in December 1924. The prosecution believed the testimony to be a complete fabrication and raised questions about why the couple would make such an unlikely trip to rural Indiana in the middle of the winter. E. B. Schultze, the wife of another local Klan organizer, testified that Stephenson and Madge had visited her house in November 1924 (two months before Madge said she first met Stephenson) and that Madge called Stephenson "dear" and "Stevie."

Ralph Rigdon, a close political friend of Stephenson, provided the most surprising testimony, placing Madge and D. C. together in a hotel suite enjoying gin weeks before the alleged assault. In cross-examination, defense attorney's labeled Rigdon's testimony "a plain lie" and soon a shouting match between attorneys erupted that finally led to Judge Sparks cautioning, "Now gentlemen, ...if you can't conduct yourself properly on both sides, I am going to get somebody that will!" Following more testimony--and more heated exchanges--with Rigdon, the defense produced two more witnesses who also placed Madge and Stephenson together on occasions well before the ill-fated train trip to Hammond. On November 10, 1925, the defense rested.

Summations and Verdict

In his three-hour-long summation, Will Remy quoted the defendant: “I am the law.” He told the crowded courtroom that the defendants "destroyed Madge's body, tried to destroy her soul" and over the course of the trial tried to "befoul her character." He called the testimony of various defense witnesses (part of Stephenson's "gang") who tried to tarnish Oberholtzer's reputation nothing but a "maze of lies and artifices." He told jurors they should convict the defendants of murder because their refusal to provide immediate care after Madge's poisoning "hastened her death." He accused the defense to trying to assassinate Madge’s character “and yet . . .Madge Oberholtzer’s story still stands. Untarnished.” Madge might well have been saved, Remy said, except for her mangling by “the fangs of D.C. Stephenson.”

For the defense, Ira Holmes argued that "suicide is not a crime in Indiana" and therefore the defendants cannot be considered accessories. He questioned the accuracy of Madge's dying declaration, telling jurors that the words in the document "originated in the mind of Asa Smith." As for the prosecution's claim of premeditation, Holmes argued that because Stephenson did not "force her to take poison."

Charles Cox, in the state's second summation, described Stephenson as "a sadist and moral degenerate" who "should be killed by the law." Let free, he warned jurors, these perverts would "commit other outrages." But, he told jurors, "You won't let them do it."

Closing next for the defense, Floyd Christian argued that Madge's death was a suicide for which his clients bore no criminal responsibility: "If a man went home and committed suicide because his banker refused to lend him money, you wouldn't hang the banker. It would be a plain case of suicide, as this is. Suicide can't be homicide."

Eph Inman, summing up next, claimed "there is some mysterious power in this state that is back of the persecution of this men." He argued that Madge had several opportunities to escape her "captors," such as when she was in the drug store buying mercury tablets. He said that because of her own actions--failure to flee or seek help, failure to immediately tell Stephenson that she ingested mercury--she, rather than the defendants, bore responsibility for her own death. Inman said that the defendants had already "suffered far too much" and that the jurors have a duty to make sure no "more harm comes to these men."

Finally, wrapping up for the state, Ralph Kane concluded his emotional speech by asking "whether there's a man in this community who would sign a verdict to acquit this hideous monster who preys on the virtuous young daughters of our state!"

On November 14, 1925, after five hours of deliberation, jurors filed into their courtroom to announce their verdicts: Stephenson was found guilty of second degree murder. The only discussion among jurors, it turned out, was whether to convict Stephenson of first or second degree murder. Four jurors had held out for sending Stephenson to the electric chair. Klinck and Gentry were acquitted. Stephenson, leaving the courtroom, told a reporter, "Hell, we've only begun to fight!" His attorney, Floyd Christian, added, "Of course we will appeal." One week later, having been sentenced to life, Stephenson heard the gates of Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana slam shut behind him.

Epilogue

Stephenson counted on a pardon from his friend and political ally, Governor Ed Jackson. Political calculations for Jackson, however, were far different than they had been before the Oberholtzer assault. D. C. Stephenson was no longer a popular man in Indiana. No pardon came.

In July 1927, in revenge for not getting his expected pardon, Stephenson released to the press "little black boxes" containing the names and incriminating records of political leaders in Indiana who had been on the Klan payroll. The information led to the indictment of Governor Jackson and other public officials. The resulting publicity also led to a crackdown on the Klan and its influence in the state rapidly declined.

The Stephenson appeal was not decided by the Indiana Supreme Court until 1932. With three justices dissenting, the Supreme Court affirmed the conviction.

Stephenson was paroled in 1950, but arrested again just eight months later and sentenced to another ten-year term. In 1956, Stephenson was discharged from prison a second time. In 1961, in Independence, Missouri, Stephenson was arrested on charges of attempting to sexually molest a sixteen-year-old girl. The man who once said he "was the law in Indiana" died on June 28, 1966 in Jonesborough, Tennessee.

The Klan, meanwhile, entered a downward spiral, its membership and political influence in swift decline.

Note: The first draft of this account relied on numerous sources listed in the bibliography, the best of which being Grand Dragon: D. C. Stephenson and the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana by M. William Lutholtz (Purdue Univ. Press, 1991.) More recently, Timothy Egan has published a riveting account of the trial, A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan's Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them (Viking Press, 2024).