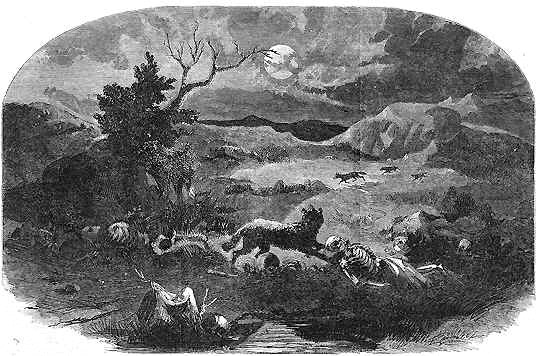

Called "the darkest deed of the nineteenth century," the brutal 1857 murder of 120 men, women, and children at a place in southern Utah called Mountain Meadows remains one of the most controversial events in the history of the American West. Although only one man, John D. Lee, ever faced prosecution (for what probably stands as one of the four largest mass killings of civilians in United States history), many other Mormons ordered, planned, or participated in the massacre of wagon loads of Arkansas emigrants as they headed through southwestern Utah on their way to California. Special controversy surrounds the role in the 1857 events of one man, Brigham Young , the fiery prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who led his embattled people to the "promised land" in the valley of the Great Salt Lake. What exactly Brigham Young knew, and when he knew it, are questions that historians still debate.

The tragedy in Mountain Meadows on September 11--a date that would later come to stand for another senseless loss of life--can only be understood in the context of the colorful history of the most important American-grown religion, Mormonism. Today, Mormonism has gone mainstream and Mormons seem to be just one more strand among many in the nation's religious fabric. Mormonism, however, as it existed in the mid-nineteenth century, was an altogether different matter. Brigham Young's provocative communalist religion endorsed polygamy, supported a theocracy, and advocated the violent doctrine of "blood atonement"--the killing of persons committing certain sins as the only way of saving their otherwise damned souls. It is not surprising that practicioners of such a religion might grow suspicious of persons outside of their religious community, nor should it be surprising that non-Mormons living in, or traveling through, the very Mormon territory of Utah might feel like "strangers in a strange land."

In July 1847, seventeen years after Joseph Smith and a group of five other men founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New York and three years after an Illinois lynch mob killed Smith, Brigham Young and his band of followers entered Salt Lake valley. When a territorial government was formed in Utah in 1850, Young, the second head of the Church of Latter-day Saints, became the territory's first governor. The principle of "separation of church and state" carried little weight in the new territory. The laws of the territory reflected the views of Young. In a speech before Congress, federal judge and outspoken Mormon critic John Cradlebaugh said, "The mind of one man permeates the whole mass of the people, and subjects to its unrelenting tyranny the souls and bodies of all. It reigns supreme in Church and State, in morals, and even in the minutest domestic and social arrangements. Brigham's house is at once tabernacle, capital, and harem; and Brigham himself is king, priest, lawgiver, and chief polygamist."

Rising Tensions

Tensions between federal officials and Mormons in the new territory escalated over time. Historian Will Bagley, author of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, wrote that "the struggle often resembled comic opera more than a political battle." According to Bagley, "As both sides talked past each other, hostile rhetoric fanned the Mormons resentment of government. From their standpoint, they had patiently endured two decades of bitter persecution with great forbearance, but their patience with their long list of enemies had worn thin." As early as 1851, Governor Young said in a speech, "Any President of the United States who lifts his finger against these people shall die an untimely death and go to hell!"

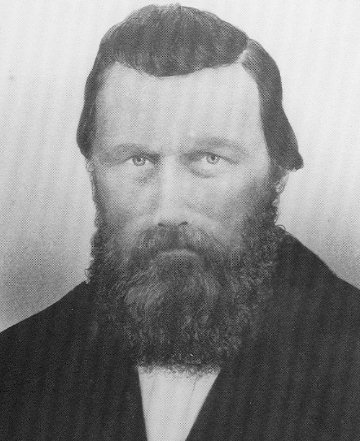

Brigham Young

When drought and grasshopper infestations produced desperate economic conditions in Utah (or Deseret, as the Mormons called the territory), Brigham Young concluded that the problem stemmed from a loss of righteousness among his people. In early 1856, Young launched the Reformation, a campaign to arouse religious consciousness. Mormon leadership urged spiritual repentance and rebaptisms. All those unwilling to make the necessary religious sacrifices were invited to leave Utah. The most troubling aspect of the Reformation was its obsession with the doctrine of blood atonement. Young asked his followers to kill Mormons who committed unpardonable sins: "If our neighbor...wishes salvation, and it is necessary to spill his blood upon the ground in order that he be saved, spill it." While Young aimed his fiery words about blood atonement at Mormons who committed serious sins, his speeches undoubtedly contributed to a growing culture of violence. The Reformation might have had a spiritual goal, but it fueled a fanaticism that led to the tragedy at Mountain Meadows.

In 1857, conflict between the Mormon leadership and Utah and the federal government reached the boiling point. Worried that a federal army might be sent to the territory, the Mormon-dominated Utah legislature enacted legislation in January reactivating the territorial militia, called the Nauvoo Legion. Federal officials in Utah complained of harassment and destruction of records by Mormon citizens. On April 15, 1857, a federal judge, the territorial surveyor and the U. S. Marshal (all the federal officials in Utah except one Indian agent) fled the state, convinced that they were about to be killed. President James Buchanan responding by ordering an army to Utah to quell what he called a "rebellion."

Buchanan's order alarmed Utah's Mormon population, who saw it as nothing less than a threat to the existence of their religion. Past persecution experienced by Mormons in the Midwest made the danger seem especially real. Church officials referred to Federal officials and the U. S. army as "enemies," and Utahans readied for what many saw as a life-or-death struggle for their faith. Young embarked on an effort to rally Indian support for the Mormon cause--support that he saw as potentially critical in the battle to come.

Meanwhile, several extended families left Arkansas by wagon train on what they planned to be their long emigration to southern California. Unfortunately for the groups of families (which came to be called "the Fancher party"), a revered Mormon apostle (and the great-great grandfather of 2008 Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney), Parley Pratt, was murdered in western Arkansas within two weeks of their departure. News of the Pratt murder, committed by a non-Mormon angered over Pratt's taking of his wife, soon reached Utah, and greatly inflamed local hostility toward non-Mormons. When further word reached Salt Lake in July 1857 that the army was headed its way, Utah became a place hungry for retribution.

On September 1, 1857, Brigham Young met in Salt Lake City with southern Indian chiefs. According to an entry in the diary of Dimick Huntington, Young's brother-in-law who was present at the meeting, Young encouraged the Indians to seize "all the cattle" of emigrants that traveled on the "south route" (through southern Utah) to California. (The journal entry actually says Young "gave" the Paiute chiefs the emigrant's cattle.) The meeting increased the likelihood of a violent encounter between Indians and emigrants, something Young apparently saw as a useful shot across the federal government's bow. In fact, Young had been working on such a plan even before his September 1 meeting, having sent apostle George A. Smith south with instructions to let the Indians know that Young considered emigration through Utah a threat to the well-being of both Mormon and Indian residents of the territory.

George A. Smith

The same day that Young talked with Paiute leaders, the Fancher Party, consisting of about 140 Arkansans, camped about seventy miles north of Mountain Meadows. On the Fancher party's way through Utah, rumors spread that some of its members participated in the killing of Parley Pratt and the lynching of Joseph Smith in Illinois. John D. Lee, a Mormon living in southern Utah, believed the stories to be true: "This lot of people had men amongst them that were supposed to have held kill the prophets in the Carthage jail." (Later, in attempts to rationalize the slaughter, Utahans would accuse the Fancher party of committing all sorts of manufactured sins and depredations: "tormenting women," swearing, insulting the Mormon Church, brandishing pistols, and even poisoning cattle. There is virtually no evidence to support any of these charges. Undoubtedly, the Fancher party understood it was not welcome in the territory and simply wanted to get out as fast as possible.)

On September 4, Cedar City was gripped in the white heat of fanaticism as the Fancher train rolled into the southwestern Utah town. The wagon train's imminent arrival had prompted Isaac Haight, second in command of the Iron Brigade (the Nauvoo Legion's force in southern Utah) and President of the Cedar City Stake of Zion (the highest Mormon ecclesiastical official in southern Utah), to call a meeting to discuss the course of action to be taken against the emigrants. According to Lee's later account of the meeting, Haight said it was "the will of all in authority" to arm Paiute and incite them to "kill part or all" of the party. Haight sent Indian interpreter Nelphi Johnson off on a mission to "stir up" the Indians so that they might "give the emigrants a good hush." Haight shed no tears for the party's fate, telling Lee, "There will not be one drop of innocent blood shed, if every one in the damned pack are killed, for they are the worse lot of outlaws and ruffians that I ever saw in my life."

Isaac Haight

Sunday, September 6 was a day for dramatic speech making at Mormon services around Utah. In Salt Lake City, Brigham Young took the occasion to declare that the Almighty recognized Utah as a free and independent people, no longer bound by the laws of the United States. In Cedar City, meanwhile, Isaac Haight told those gathered at the morning service that "I am prepared to fee to the Gentiles the same bread they fed to us. God being my helper, I will give the last ounce of strength and if need be my last drop of blood in defense of Zion." That Sunday evening, the Fancher party crossed over the rim of the Great Basin and encamped at a place called Mountain Meadows.

The next morning's calm at the meadows was interrupted by gunfire. A child who survived the attack wrote later, "Our party was just sitting down to a breakfast of quail and cottontail rabbits when a shot rang out from a nearby gully, and one of the children toppled over, hit by a bullet." The shots came from forty to fifty Indians and Mormons disguised as Indians. The well-armed emigrants returned fire. Soon the gun battle turned into a siege. Meanwhile, in Cedar City, Isaac Haight, responding to pressure from Mormons lacking enthusiasm for the attack on the emigrants, sent a courier on a 600-mile trip (that will take six days, round trip) to inform Brigham Young of the situation at Mountain Meadows and ask his guidance about what to do next.

Col. William Dame and his wives

Over the next three days, Mormon reinforcements, totally about 100 men, continued to arrive at the battle scene. Men on horseback carried messages back to Haight, and his immediate superior in the Nauvoo Legion and head of southern Utah forces, William Dame. Dame reportedly reiterated his determination to not let the emigrants pass: "My orders are that all the emigrants [except the youngest children] must be done away with." On September 10, the messenger send to Salt Lake City arrived and handed Haight's letter to Young. Young, according to published Mormon reports, sent the messenger back to Haight with a note telling him to let the Indians "do as they please," but--as for Mormon participation in the siege--if the emigrants will leave Utah, "let them go in peace." The message will be too late.

The Massacre

By September 11, Legion officers had devised a plan for ending the stand-off. Most of the Paiutes had left after growing weary of the siege and could play no role in the bloody conclusion. The plan was devious, but effective. Major John Higbee, in command of the forces at Mountain Meadows, persuaded John Lee and William Bateman to act as decoys to draw the emigrants out from the protection of their wagons. Lee and Bateman, carrying a white flag, marched across the field to the emigrants' camp. The desperate emigrants agreed to the terms promised by Lee: They would give up their arms, wagons, and cattle, in return for promise that they would not be harmed as they embarked on a 35-mile hike back to Cedar City. Samuel McMurdy, a member of the Nauvoo Legion, took the reigns of one of the wagons into which were loaded some of the youngest children. A woman and a few seriously injured emigrant men were loaded into a second wagon. John Lee positioned himself between the two wagons as they pulled out. Following the two wagons, the women and the older children of the Fancher party walked behind. After the wagons had moved on, Higbee ordered the emigrant men to begin walking in single file. An armed Mormon "guard" escorted each emigrant man.

Maj. John M. Higbee

When the escorted men had fallen a quarter mile or so behind the women and children, who had just crested a small hill, Higbee yelled, "Halt! Do your duty!" Each of the Mormon men shot and killed the emigrant at his side. Meanwhile, on the other side of the hill, Nelphi Johnson shouted the order to begin the slaughter of the women and older children. Men rushed at the defenseless emigrants from both sides, and the killing went on amidst "hideous, demon-like yells." Nancy Huff, four years old at the time of the massacre, later remembered the horror: "I saw my mother shot in the forehead and fall dead. The women and children screamed and clung together. Some of the young women begged the assassins after they run out on us not to kill them, but they had no mercy on them, clubbing their guns and beating out their brains." It was over in just a few minutes. 120 members of the Fancher party were dead. The youngest children, seventeen or eighteen in all, were gathered up, to later be placed in Mormon homes. None of the survivors were over seven years old.

Looking to site of Fancher camp and siege from Dan Sill hill

The next day, Colonel Dame and Lt. Colonel Haight visited the site of the massacre with John Lee and Philip Klingensmith . Lee, in his confession, described the field on that day: "The bodies of men, women and children had been stripped entirely naked, making the scene one of the most loathsome and ghastly that can be imagined." Dame appeared shocked by what he found. "I did not think there were so many of them [women and children], or I would not have had anything to do with, Dame reportedly said. Haight, angered by Dame's remark, expressed concern that Dame might try to blame him for an action that Dame had ordered. The men agreed on one thing, however: Mormon participation in the massacre had to be kept secret. Within twenty-fours hours, Haight had another reason for concern. Brigham Young's reply to his inquiry arrived in Cedar City. "Too late, too late," Haight said as he read Young's letter and began to cry.

Brigham Young declared martial law on September 15. In his proclamation (of dubious legality), Young prohibited "all armed forces...from entering this territory" and ordered the Nauvoo Legion to prepare for an expected invasion by federal forces. The proclamation also prohibited any person from passing through the territory without a permit from "the proper officer."

Shortly after his proclamation, Young learned of the tragic events at Mountain Meadows, first from Indian chiefs and then from John Lee, who traveled to Salt Lake City to provide a detailed account of the massacre. According to Lee, Young at first expressed dismay about the Mormon participation in the massacre. He seemed especially concerned that news of the massacre would damage the national reputation of the Latter-day Saints The next day, however, Young said he was at peace with what happened. According to Lee, Young said, "I asked the Lord if it was all right for the deed to be done, to take away the vision of the deed from my mind, and the Lord did so, and I feel first rate. It is all right. The only fear I have is from traitors."

Response to the Massacre

The first published reports of the massacre begin appearing in California newspapers in October. One came from John Aiken, who with mail carrier John Hunt, passed by Mountain Meadows in late September with a pass signed by William Dame. Aiken wrote, "I saw about twenty wolves feasting upon the carcasses of the murdered. Mr. Hunt shot at a wolf, and they ran a few yards and halted. I noticed that the women and children were more generally eaten by the wild beasts than were the men." The Los Angeles Star called it the "foulest massacre ever perpetrated," and added that responsibility for the attack "will not be known until the Government makes a full investigation of the affair." The San Francisco Bulletin was far less restrained, calling for "a crusade against Utah which will crush out this beast of heresy forever." Public outrage grew. Americans from California to Washington, D. C. begin calling for military action against those responsible for the crime.

Sketch of massacre site that appeared in Harper's Weekly issue of 8/13/1859

Aware of the sensitivity of the events at Mountain Meadows, Mormon officials from Young on down worked to shift the blame for the massacre either to Indians or the emigrants themselves. By November, John Lee completed a fictionalized account of the massacre, attributing all the killing to Indians, and sent the report on to Young. Young, as Superintendent of Indians in addition to his other titles, prepared a report blaming the massacre on the mistreatment of Indians by non-Mormons, and sent it on to the Indian Commissioner. "Capt. Fancher & Co. fell victim to the Indians' wrath near Mountain Meadows," Young wrote. "Lamentable as the case truly is, it is only the natural consequences of that fatal policy which treats Indians like wolves, or other ferocious beasts."

None of the Mormon-drafted reports, however, prevented Congress from debating the massacre. On March 18, 1858, Congress ordered an official inquiry into the cause of the tragedy of September 11. The next month, one fourth of the United States army reached Fort Bridger, in present-day Wyoming. Rather than fight the Nauvoo Legion forces guarding the canyons leading to Salt Lake, General Albert Alston decided to overwinter at the Fort. President Buchanan expressed his determination to put down the "rebellion" in Utah, with force if necessary: "Humanity itself requires that we should put it down in a manner that it shall be the last."

In this dark moment of Mormon history, Brigham Young had the good fortune in April 1858 of being replaced as Governor of Utah by Alfred Cumming, a gullible man who believed Young's promise to get to the bottom of the Mountain Meadows matter, and who established, as his principal goal, preserving peace in the Utah territory. Governor Cumming planned a trip south to Mountain Meadows almost as soon as he took office to investigate "that damned atrocity," as he put it. Young, in a visit to Cumming's office, succeeded in convincing the governor of his genuine desire to identify the perpetrators. Cummings decided to put "the whole matter" in Young's hands, trusting him "to put the finger upon the miscreants." He also recognized, as he later told Young, "I can do nothing here without your influence." Pushing to open again free emigration on the south route, Cummings took pleasure in announcing on May 11, "the Road is now open." Over time, Cummings became convinced that the threats to the territory's peace of an aggressive inquiry into the Mountain Meadows massacre, in his mind, outweighed the benefits. He also lacked the will to challenge Young and was, in the words of one observer, "mere putty" in the Mormon leader's hands.

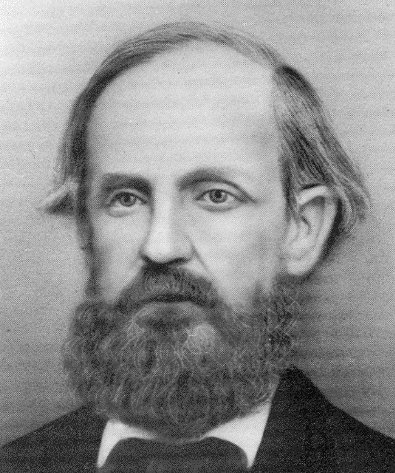

Federal Judge John Cradlebaugh

In the latter half of 1858, the federal government began to reassert some measure of federal control in the Utah territory. On June 26, federal troops marched through Salt Lake City, on their way to a fort forty miles from the city under the terms of a deal brokered with Young. (The deal included a pardon for those acts considered part of "the rebellion.") In November, U. S. District Judge John Cradlebaugh arrived in Utah and, unlike the governor, saw no reason not to aggressively pursue justice for the victims of the Mountain Meadows massacre. After several months of investigation, Judge Cradlebaugh issued arrest warrants for John Lee, Isaac Haight, and John Higbee for the murders. Angered by his discovery that the massacre was committed "by order of council," the judge wrote a letter to President Buchanan seeking his commitment to secure convictions for the guilty. Cradlebaugh's efforts, however, were frustrated when the federal case is essentially dropped after the U. S. marshal declared his unwillingness to execute arrest warrants without federal troops to protect him from local citizens--and that help was not provided.

By 1860, with the Union ready to split apart, interest in prosecuting the Mountain Meadows case waned. Governor Cumming saw little reason to press for prosecution, especially in a territory where the law put jury selection entirely in the hands of Mormon officials. "God Almighty couldn't convict the butchers unless Brigham Young was willing," Cumming said.

The Trials of John D. Lee

Renewed interest in the Mountain Meadows case developed in the early 1870s, thanks largely to a series of stories in the Utah Reporter by Charles W. Wandell, writing under the pen name "Argus," that challenged Brigham Young's response to the massacre. Wandell's articles produced the first confession in the case when, on April 10, 1871, Philip Klingensmith, a former LDS bishop who subsequently left the Church, appeared in a Nevada court and swore out an account of the massacre, including a detailed description of his own role in the crime. Still, however, Mormon control of the Utah justice system stymied any prosecution in Utah.

Phillip Klingensmith, Bishop of Cedar City

The key to a possible successful prosecution finally came in 1874. Congress passed the Poland Act, which redefined the jurisdiction of the courts in Utah. The law restricted the authority of Mormon-controlled probate courts and opened all Utah juries to non-Mormons.

Within months of passage of the Poland Act, arrest warrants for nine men: Lee, Higbee, Haight, Dame, Klingensmith, Stewart, Wilden, and Jukes. Federal authorities arrested John Lee, long considered Mormon officials' most likely candidate for scapegoat for the massacre, after finding him hiding in a chicken coop near Panguitch, Utah, on November 7, 1874. Shortly thereafter, Dame was also arrested. The best prospects for conviction seemed to rest with Lee, so the decision was made to proceed first with his trial.

The First Trial

The trial of John D. Lee opened on July 23, 1875 before U. S. District Judge Jacob Boreman in Beaver, Utah. Talk of possible mob action against witnesses filled the crowded streets of Beaver. Marshal Maxwell sought to preserve order by threatening potential instigators: "We will hang any god damned Bishop to a telegraph pole and turn their houses over their heads." The crowd, the bailiff reported to Judge Boreman, got the message that the government meant business.

U. S. attorneys William C. Carey and Robert Baskin managed the prosecution, while four attorneys--bankrolled by Brigham Young--comprised Lee's defense team. Marshal Maxwell sought to preserve order by threatening potential instigators: "We will hang any god damned Bishop to a telegraph pole and turn their houses over their heads." Throughout the trial, conflicts arose among Lee's lawyers, with two members of the defense team (including Wells Spicer who, six years later as a magistrate in Tombstone, ruled--after a several week hearing--that the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday should face a criminal trial for the famous "shoot-out at the O.K. Corral") determined to provide Lee with his strongest possible defense even if it meant implicating higher Mormon officials, while two other members of the team seemed equally focused on protecting those same higher officials. The jury, gathered in the improvised courtroom on the second floor of the Beaver City Cooperative, consisted of eight Mormons, one former Mormon, and three non-Mormons.

After Carey opened the case for the prosecution with a compelling description of the massacre, a parade of witnesses took the stand to describe various aspects of a concerted plan by Mormon officials to make life for emigrants traveling through Utah in 1857 as difficult as possible. Several witnesses testified that they had received orders not to sell grain or provisions to the Fancher party. One witness said he was hit over the head by fence paling because he sold onions to one member of the party who was a friend of his from years back. Another witness testified Church officials excommunicated him after he traded one emigrant cheese for a bed quilt. Still other witnesses recalled the fiery sermons of George A. Smith and other Church leaders, all warning of the threats posed by emigration through the state, in that 1857 summer of high passions and fanaticism.

The prosecution's star witness was Philip Klingensmith, the former bishop of Cedar City and the apostate Mormon whose affidavit given in a Nevada courtroom had first renewed hopes of achieving long-delayed justice in the Mountain Meadows case. The heavyset Klingensmith began his account slowly, but his emotions showed as the events he described moved toward their tragic climax. He recounted how the Mormon men responded to the militia call by traveling to the emigrant's camp by wagon and horseback. He told of the men watching in formation as John Lee conducted his "negotiations" with the emigrants. Finally, he described the killing. From his vantage point, he could see only the shooting of the men; Lee was over the crest of the hill with the wagons and the women and children. About fifty of the emigrant men, Klingensmith testified, died with the first volleys from their "guards." A few started to run away, but none got very far. Lee appeared downcast as the prosecution's chief witness told his story of death. Klingensmith said Lee and the other men acted on orders from Higbee, which had come from Isaac Haight, and--in turn, he thought--from Dame. The former bishop testified that a few weeks after the massacre he was among a group of Mormons that met with Brigham Young. Young, he said, discussed how the emigrant's property should be divided and counseled them against discussing the massacre: "What you know about this affair do not tell to anybody; do not even talk about it among yourselves."

For the defense, Wells Spicer presented Lee as a reluctant participant. He said the bad behavior of the emigrants was largely responsible for the massacre, and that Lee had cried and "tried to protect the emigrants" when their killing had first been proposed by Haight and Higbee. Lee only did what he did, Spicer said, after having John Higbee aim a loaded rifle at his head. According to the defense attorney's version of events, hundreds of Indians at Mountain Meadows forced the few dozen white men into helping in the killing: "if they didn't, the Indians would kill them and sweep off their homes, and families and settlements."

In the trial's oddest turn of events, Spicer came back after a courtroom recess to withdraw all his remarks concerning Lee's having acted under orders. Spicer's 180-degree turn, according to a report of the trial, "left the gentlemen of the jury in a hapless state of mystification." Clearly, some people were not at all happy that Spicer had adopted a strategy of pointing fingers at higher officials.

The defense never presented a cohesive story of the massacre itself. Instead, it presented witnesses that testified that members of the Fancher party had done things to earn the enmity of local Indians. One witness claimed to have seen members of the wagon train leave bags of poison by a spring at Corn Creek. The defense witness testified that Indians told him that members of their tribe had died after drinking poisoned water from the spring. On cross-examination, however, the defense's poison story fell apart. In his summation, defense attorney Jabez Sutherland said the massacre was all the doing of the righteously angered Paiutes: "[The Indians] were implacable in their wrath, and even threatened the Mormons for their efforts to pacify them."

The prosecution, in Brigham's Young's Utah with a jury that included eight Mormons, never expected a guilty verdict--and they didn't get one. The jury hung, with the eight Mormons and the one former Mormon voting to acquit Lee, and the three non-Mormons voting to convict. A newspaper in Idaho presented a typically cynical view of the trial's outcome: "It would be as unreasonable to expect a jury of highwaymen to convict a stage robber as it would be to get Mormons to find one of their own peculiar faith guilty of a crime."

The Second Trial

What a difference a trial makes: the second trial of John D. Lee bore almost no resemblance to the first. Mormon witnesses against Lee suddenly materialized in the second trial, many with enhanced memories that put Lee in the middle of the killing. The prosecutors, in a rejection of the strategy in the first case which placed shared blame well up the Mormon command chain, suddenly seemed only too willing to present Lee as the driving force behind the massacre. What happened?

What happened, apparently, is that a deal--or at least an understanding--was reached. In April 1876, Sumner Howard replaced William Carey as the U. S. Attorney for Utah. Under pressure from Washington and the public to convict someone for the massacre, Howard pondered how a unanimous jury verdict could ever be achieved in the case without Brigham Young giving the prosecution his blessing. It couldn't, he concluded. An agreement with Young had to be struck. Howard and Young met in Salt Lake. Young was anxious to put the Mountain Meadows matter behind and accepted that someone had to be sacrificed. The excommunicated Lee was the obvious candidate. The terms of the agreement between Howard and Young were never disclosed, but former U. S. attorney Robert Baskin outlined his speculation as to the key understandings. Baskin believed that Howard agreed to impanel an all-Mormon jury, place Brigham Young's 1875 affidavit in evidence, present testimony that would tend to exonerate higher Mormon officials, and--after trying Lee--promised to prosecute no one else for what happened at Mountain Meadows. In return, Young would help round up witnesses who would incriminate Lee and see to it that the jury returned a conviction. (Not everyone is willing, however, to accept Baskin's speculation as truth. Howard denied that a deal had been struck in a letter he sent to Attorney General Taft. Howard instead suggested that Lee's attorney manufactured the deal theory in a last-ditch attempt to gain sympathy for his client. Critics of the deal theory also note that the government made some efforts--although rather half-hearted--to pursue other massacre perpetrators until 1888, when the case was finally dropped.)

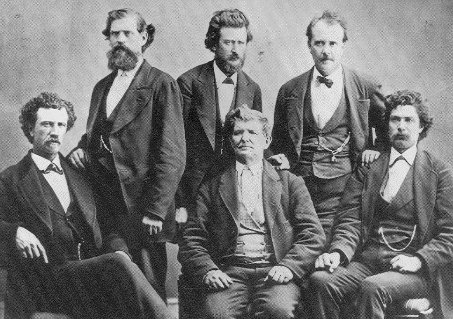

John Lee and his legal team with presiding judge (Lee in center, lead defense attorney William Bishop at far left, next to Bisop is presiding judge Jacob Boreman, Wells Spicer is in upper right)

The second trial began on September 14, 1876, soon after the prosecution dropped all charges against William Dame. Jury selection went quickly, as a report sent to Brigham Young noted: "Howard made no effort to get Gentiles on the Jury--In fact the word Mormon was scarcely mentioned in court all day." The surprising turn of events--the Church aiding the prosecution--left Lee's defense attorney, William Bishop, angry and confused. Before the trial began, Bishop assumed that the Mormon leadership would protect his client. Writing a few months after trial, Bishop's anger poured out: "I claim that Brigham Young is the real criminal, and that John D. Lee was an instrument in his hands. That Brigham Young used John Lee, as the assassin uses the dagger to strike down his unsuspecting victim; as as the assassin throws away the dagger, to avoid the bloody blade leading to his detection, so Brigham Young used John Lee to do his horrid work; and when the discovery becomes unavoidable, he hurls Lee from him...and casts him far out into the whirlpool of destruction."

From its opening statement on, the prosecution made clear that its goal was to convict John Lee, not try the entire Mormon hierarchy. The prosecution case made Lee to appear even more guilty than he was. Lee incited the Indians to attack the wagon train. Through deception, Lee lured other Mormons into the battle. Lee hatched the plan that led to the massacre. Lee himself killed a number of emigrants, then helped divide the plunder. Out of the Utah woodwork came a whole host of loyal Mormons ready to testify as to Lee's bad deeds. Samuel Knight testified that he watched Lee club a woman to death. Samuel McMurdy said he saw Lee shoot a woman, as well as two or three of the wounded emigrants. Jacob Hamblin told the court he witnessed Lee throw down a girl "and cut her throat." Nelphi Johnson testified that Lee and Klingensmith seemed to be "engineering the whole thing."

Lee could do little against the onslaught but complain. Pacing his cell floor during a break in the trial, Lee bitterly complained that witnesses were charging him with "awful deeds...that they did with their own wicked hands." Everyone could see the game plan: the buck stops with Lee. The memories of witnesses memories suddenly faded when asked to name other Mormons present at the battle see. No one could remember who else might have participated in the killing.

Resigned to his fate, Lee asked his attorneys to present no defense after the prosecution closed its case. With little evidence from which to draw, William Bishop in his summation could only note the obvious: "The Mormon Church had resolved to sacrifice Lee, discarding him as of no further use." On September 20, 1876, at 3:30 in the afternoon in Beaver, the all-Mormon jury returned its verdict. John Lee was guilty of murder in the first degree.

The Execution

When asked by Judge Boreman if he wished to say anything prior to sentencing, Lee remained silent. Boreman sentenced Lee to be executed in three weeks. Lee told the judge, "I prefer to be shot."

Appeals delayed Lee's scheduled execution over five months. Lee used much of the time to write his autobiography. On a March afternoon in 1877 in Beaver, Utah, U. S. Marshal William Nelson led John Lee to a closed carriage that would take him south over the emigrant trail to Mountain Meadows. On March 23, Lee, dressed in a red flannel shirt, enjoyed breakfast and a cup of coffee near the site of the 1857 massacre. A minister walked the condemned man to his own coffin. Lee sat down on the coffin while the Marshal read his death warrant. When the reading ended, he rose to address the federal officers, firing squad, and seventy or so spectators.

"I feel as calm as the summer morn," Lee told the gathering, "and I have done nothing intentionally wrong. My conscience is clear before God and man....Not a particle of mercy have I asked of the court, the world, or officials to spare my life. I do not fear death, I shall never go to a worse place that I am now in...I am a true believer in the gospel of Jesus Christ. I do not believe everything that is now being taught and practiced by Brigham Young. I do not care who hears it. It is my last word--it is so. I believe he is leading the people astray, downward to destruction. But I believe in the gospel that was taught in its purity by Joseph Smith...I have been sacrificed in a cowardly, dastardly manner....Having said this, I feel resigned. I ask the Lord, my God, if my labors are done, to receive my spirit."

John Lee seated on his coffin moments before his execution

Lee shook hands with those around them and resumed his seat on his coffin. He shouted to the firing squad, hidden in three wagons forming a semi-circle around him: "Center my heart, boys! Don't mangle my body!" When the shots came, he fell back without a cry.

Epilogue

Five months after Lee's execution Brigham Young died. The cause of death was uncertain, but appendicitis was suspected.

William Bishop, Lee's attorney in his second trial, sent the manuscript Lee had completed in prison to a publishing company in St. Louis. In 1877, Mormonism Unveiled or the Life and Confession of John D. Lee became an immediate bestseller. The book provided an important history of early Mormonism as well as offering Lee's somewhat self-serving account of the events leading to the Mountain Meadows massacre. As historian Will Bagley noted, Lee "reconstructed his chronology to distance himself from the initial attack" and provided blistering attacks on the men who testified against him. Lee's list of murderers, aside from those who admitted killing emigrants, included only his enemies.

In 1998, Gordon B. Hinckley, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, visited Mountain Meadows. He found himself embarrassed at the dilapidated condition of monument at the site and committed the Church to building a proper memorial. "We owe [the dead] respect," Hinckley declared, "that land is sacred ground." On September 11, 1999, a new monument was dedicated at Mountain Meadows. President Hinckley, in the afternoon sunshine, told the assembled crowd: "[The past] cannot be recalled. It cannot be changed. It is time to leave the entire matter in the hands of God."

The best source for more information about the Mountain Meadows Massacre and the subsequent investigations and trials is:

Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Mountain Meadows Massacre by Will Bagley (Univ. of Oklahoma Press 2002).